POWER FOR ALL

Just as it was feared a universal supply of safe drinking water to the City’s residents would confer some sort of legitimacy on the Walled City as a whole, so it was with the installation of a safe and reliable electrical supply. The Government decided to supply water through a strictly limited number of standpipes, which while undoubtedly inconvenient was relatively safe. The same solution, however, would not work with electricity.

The danger of not providing electricity to those who needed or wanted it had been brought home to the Hong Kong Government following a huge fire at the Shek Kip Mei ‘squatter’ settlement (in reality refugees from China) on Christmas Day 1953, which left over 50,000 people homeless. Up until that time, electricity had not been supplied to such settlements, forcing their inhabitants to rely on Kerosene lamps and stoves for lighting and cooking. This could not be allowed to continue and over the next few years China Light and Power gradually installed a permanent supply to all Hong Kong residents, regardless of status and location – including the Walled City.

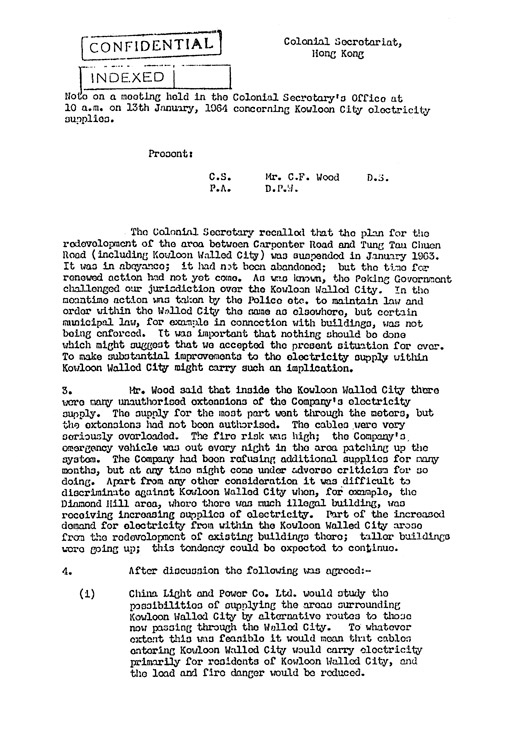

Even then, the supply to the Walled City remained far less than demand required. A Government memo of January 1964 noted that: “inside the Kowloon Walled City there were many unauthorised extensions of the Company’s electricity supply. The cables were very seriously overloaded. The fire risk was high; the Company’s emergency vehicle was out every night in the area patching up the system.”

Somewhat grudgingly China Light and Power was allowed greater access, but an increased supply only engendered greater demand, leaving the Company forever struggling to keep up. In fairness, this situation applied to Hong Kong as a whole during a decade of dramatic growth, but the situation was especially acute in the Walled City and it was only in the mid 1970s that the Company decided to initiate a complete overhaul of the City’s supply.

Mok Chung Yuk was one of the company’s engineers responsible and here below are his recollections of the situation when he started working in the City in 1977. Unsurprisingly, these are not always entirely accurate, particularly with regard overall policy, but they do provide an excellent description of the practical problems of installing and maintaining a relatively safe and reliable electrical service throughout the City at that time.

“Following a big fire in the City in 1977, everyone realised things had to change. We began drafting a plan to supply electricity throughout the City and the Government established guidelines as to which buildings were acceptable. The years 1977 to ’85 were years of drastic transformation. The local District Office began to collaborate with the Kai Fong, and Government involvement in the City also increased. Later, just before the Sino-British Agreement was signed, China told the British that they could exercise full authority over the City and things became much easier.

I was one of those doing the groundwork for the new electricity supply – I carried out the very first surveys. In fact, I remember well the first time I went in – edging in a short way then turning back! It seemed very frightening at the time. We all dressed down at first, and we were careful not to enter looking like an official team. Only when we were familiar with the streets and alleys did we bring out our maps and plans. For the first few days, before we got talking to any of the locals, we just got used to the place.

We had two big worries in those early months. First, we had no idea what we would find and, second, when we found out how bad it was, we had no idea how to cope with the chaos. We quickly saw the difficulties: the narrow alleys, the filth, the rubbish, the character of the people living and working there. A few of my colleagues were robbed, possibly by drug addicts; they would even take $30. We were never really hassled by thugs though, since so many Government departments were involved in the project, including the police. And so was the Kai Fong, of course. Also, the majority of residents saw the need for electricity, so nothing unruly took place.

There were many specific technical problems. The City was just a maze of pipes and wires all over the place. We were at a loss where to begin! Eventually we decided that we’d just have to make a start from the outside and work in – take the cable and enter inch by inch. The alleys were incredibly narrow, and in places we needed to dig up the ground to lay the cable. But when we were digging we’d often strike rock or stone and have to stop. After several meetings in the City, we agreed to raise the level of the pavement instead!

We had to invent many new ways of installing cables. We’d try one way first and if that worked we’d use it again. Occasionally there’d be problems, of course. People didn’t like us fixing cables to their walls, for example, and it took some persuasion before such matters were resolved. Sometimes the wiring had to go through someone else’s premises and, of course, some saw this as an invasion. In these cases, we just had to let the applicant negotiate with the owner. Actually, in a few instances, we just supplied electricity to the power points on a lower floor and let the owner connect it to the floor above. You know what the buildings are like in the Walled City – they’re built one on top of the other, leaning here and there. In some cases, there was no way to make the necessary connections all the way up to the top floors. Of course, we’d check everything was done properly before switching on.

Hong Kong’s economy was growing fast at that time, and as everyone became better off they bought more and more electrical goods. The population was increasing fast as well. The Walled City itself was booming, with a huge amount of new construction going on. All these things contributed to an increased demand for electricity.

With more and more people in the City wanting electricity, we had to find space for the transformer we needed to cope with two high-density cables we were planning to bring in. We finally managed to persuade the church in the City to rent us around 250 square feet on condition we renovated their school. We also kept badgering the Government to release space cleared because of fires so we could build a couple more sub-stations. We discussed this with the authorities for several years, in fact, until they eventually gave us permission in 1984. It took us three years to set up the stations, by which time they had announced they were going to tear the place down!

By this time almost every flat had electricity. But that didn’t take care of all the factories. When we started out we had no idea there’d be so many. We had made provision in our plans for some excess supply, but we’d underestimated the demand – we’d often have to make spur-of-the-moment adjustments and modifications to meet requirements as we found them.

There are, of course, instances of electricity theft. Certainly, the total supply of electricity is not fully paid up or accounted for. But it’s no longer easy to steal from the Company on a large scale. When they see us, factory owners using stolen electricity are careful to hide any evidence that might give cause for suspicion. Many also realise that stolen electricity might not be that much cheaper. At least when they get their supply direct from the Company, they are never threatened or subject to extortion.

In the past, those who stole were not dealt with very effectively. This is partly because our employees didn’t dare go too far into the City! But even if action was taken, we’d usually have to bring the police in – and they did not have much authority in the place themselves. Some people claimed they had their own private power sources, which just wasn’t true! They stole from China Electric but were only rarely brought to account. If they were discovered, they’d just be disconnected.

Bringing electricity to the City was not just a unique project for Hong Kong, but pretty much anywhere I’d say. Because of the background of the place, and the conditions and environment there, we were forced to make many innovations and to problem-solve. I myself feel happy, however, that people are finally moving out, although I feel that the Government is spending far too much on compensation. When the clearance was announced, I’m sure many people moved in quickly enough to spend a couple of nights in the City, in the hope that they could benefit too.”

WATER FIT TO DRINK

Like much else in the Walled City, the provision of a reliable water supply was the source of considerable inventiveness and entrepreneurial skill, not all of it healthy. The Government’s long-standing refusal to connect individual buildings, apartments and factories into the external mains system, and thereby legalise water supplies, meant the City’s residents and businesses had to resort to paying private suppliers, to pump water from wells sunk beneath the City, or local Triad groups for water tapped illegally from nearby mains supplies.

The only concession the authorities made over the years was to install a few public freshwater stand-pipes, though these were barely enough. By 1987, just eight stand-pipes were in place to supply up to 35,000 residents and hundreds of factories. Only one of these was located within the City, while the remainder were positioned, inconveniently, outside its perimeter. Running mains water was supplied to various recognised charities inside the Walled City, but this was very much the exception not the rule.

The first stand-pipe was installed in 1963 giving the city, in the words of a Government statement at the time “access to a free, unrestricted water supply”. Residents had a somewhat different perception. Representatives of the newly formed Kai Fong Association, calling on the Secretariat for Chinese Affairs in 1964, complained of the acute shortage of water at a time when “the Chinese Government is working selflessly on the East River scheme to provide ample water for Hong Kong residents”. Their complaints were well grounded, if dressed in rhetoric. Four emergency hydrants had been removed following the end of the drought that year, leaving just five stand-pipes. Residents were paying $12 – 15 a month for labourers to carry six kerosene cans of water each day from the stand-pipes to their flats in the jumble of then mostly two- three- and four-storey buildings.

The business of carrying water for entire households became increasingly difficult the more the City grew skywards, during the boom days of the late 1960s and early ‘70s. Rapidly expanding demand, notably from new and thirsty factories, and the impracticality of trudging six or more storeys to individual apartments drove entrepreneurs underground to tap new sources. The new well diggers were mainly property owners who were able to drill on their own land; some were reputedly former water-carriers themselves.

There had been wells in the City in its earlier days. One former resident recalls water being collected from a couple of wells at the northern and eastern gates immediately after the War. By the time the clearance was announced in 1987, Government surveyors assessing compensation claims identified 67 working wells owned by some 40 suppliers. Over the years, up to 300 ‘scientific wells’ – as they are described by City-dwellers – are said to have been sunk beneath the area, though many had long run dry from overuse. The more recent drillings had to reach as far as 100 metres below the surface, as shallower sources had been depleted. Private drilling firms were contracted to carry out the work.

Physically transferring the water to residences was usually a crude, makeshift process. Water was first pumped up to rudimentary storage tanks on the City roofscape. From there, a twisted congestion of pipes ran downward again, branching into blocks and flats. Installation of a well-water link could cost as much as several thousand dollars, depending on the height above and the distance from the well. By the late 1980s, monthly charges were anywhere between $50 and $70 per household.

Despite reports of numerous people being unable to afford the steep connection fees, the majority of City residents appear to have been linked up to receive well-water. A simple connection in itself, however, did not guarantee the end to one’s water problems.

Pressure and pumping difficulties meant that many pumps would only be turned on at set times – usually noon and midnight – to replenish the tanks. This would only give a few hours’ supply, and it meant that residents still had to store water in baths and buckets. About 20 people were employed to control the supply at various locations according to the well-owner’s schedule.

Perhaps the biggest drawback with the well-water, though, was that much of it was undrinkable. Pungent and murky, it was impregnated with the usual seepage or urban and industrial pollutants. The best use it could be put to was washing and floor-cleaning; much of it was not even fit to boil. Drinking and cooking water still had to be carried from the stand-pipes, and a small workforce was engaged in this activity till the end.

Health problems were also a major concern. Before the Government got together with the Kai Fong to install a mains sewage line in the 1970s, raw human waste exited the City via open drains driven down the side of the tiny streets. Much of this sewage seeped away, forgotten, into the ground, leaving the underlying geology of the area like a giant septic tank. Underground sources, especially from the shallower wells, could not help but be contaminated.

The installation of a sewage mains was one of a number of essential services the Government felt compelled to provide. Like basic policing and lighting, and the provision of social services and rubbish removal, it was one of the several exceptions that broke the rule of non-intervention. It was, in a sense, the other necessary side of the coin to water supply, which the Government had allowed to be managed privately without regulation – extra-legally but not illegally. But sewage and waste removal was a matter of public hygiene, and had implications for the health of people beyond the City.

In later years, there were numerous calls to improve the situation by providing mains water more widely, but by then the authorities were able to cite the technical difficulties presented by the City. First among these, the Government argued, was the high concentration of buildings, none of which had adequate provision for water or waste. Second, there were the narrow streets and the sheer disruption that laying mains pipes would cause to City life. These were certainly valid considerations, but more important, perhaps, was a continuing reluctance to further encourage permanent settlement in the City, combined with the knowledge that more accessible pipework would only invite ever extending illegal connections.

Wells were not enough in themselves to supplement the eight paltry stand-pipes. Consequently there was some illegal tapping of mains water from outside the City, notably from the adjacent Sai Tau Tsuen and Mei Tung estates. This illegal business was monopolised, in the beginning, by the Triads. As these same organisations were also involved in much of the construction in the City, they were able to ensure that the newer buildings, at least, had some provision for water supply and waste – even if only of the most rudimentary kind – or could impress on the buyers the benefits of being connected.

Several competing water suppliers might also be competing for business in one building, particularly where the building was not owned by a single proprietor. Once a household was connected to a particular supplier, there were clear rules of business-client behaviour. Residents would generally pay on time for fear their water would be cut off or their pipes damaged. Fee collectors would tell customers that their dues were partly for the upkeep of the system and partly for bribes to officials. For some residents it could mean more than a simple business relationship.

The Triad leader who, in 1980, laid down the law on a price rise is one case in point. “Whoever dares to take the lead in opposing the hike”, he said, “we’ll chop him up in front of the crowd.”

In time, the Triads sold off most of their ‘business’ interest in the City, but the illegal tapping of mains water remained an important source of drinking water until the end. Those involved in the clearance are reluctant to admit how extensive this practice might have been, but it is unrealistic to assume that 33,000 people and 700 businesses could have been supplied by 67 ground wells alone. The decision was made that it was better to turn a blind eye. To close down the illegal supplies would have caused unnecessary hardship for the residents and brought increased resentment. It was easier to clear the City and solve the problem once and for all.

INTO THE MAZE

Greg and I spent over four years photographing in the Walled City, but in all that time, over all those visits, it is probably fair to say we only ever really scratched the surface. Between us we probably walked the length of nearly all the alleys at ground level, the main ones so often we got to know them well, but many of the smaller ones remained a mystery. We soon learnt that if we found something of interest in those back alleys, we had to try and photograph it there and then as the likelihood of finding the same place again was probably next to impossible.

And once you entered the buildings and started exploring the warren of stairways and interconnecting corridors that weaved their way across the City at nearly every level, the problems of finding your way increased a hundred fold. There were a few routes that ran north to south across the City at around the 7th or 8th floors that I got to know quite well, but for the rest of the time it was a case of following your nose and seeing where it led. Occasionally you would come to a dead end but usually, through a process of trial and error, you could ascend or descend a few floors and find another corridor that led off in a different direction.

Exploring the buildings in this way was a constant adventure – very quickly you had absolutely no idea which building you might be in or even which floor you might be on. The only saving grace was that, in most cases, you could follow a staircase all the way down to ground level and pop out on to an alley that you might recognise. And because the site sloped quite steeply north to south, if you still didn’t know where you were, it was relatively easy to find one’s bearings and head towards one of the four main alleys that traversed the city from Tung Tau Tsuen Road on the City’s northern boundary and the park to the south.

To give a flavour of quite what it was like to explore the City in this way, I include here just a small selection of the photographs Greg and I took on our many excursions there.

GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The Hong Kong government had attempted to clear and demolish all or parts of the Walled City in 1947 and again in 1963, but had been rebuffed both times – on the latter occasion with a formal response of disapproval from China who had made it abundantly clear that their policy with regards the City was unlikely to change in the near future.

Up until that point, the Hong Kong authorities’ approach had largely been one of minimal involvement, to the point of making life for the residents there as difficult as possible. The police made regular patrols and, following a murder in the City in 1959 that forced a change of policy, arrested and prosecuted criminals caught there – without, it should be noted, a word of protest from the Chinese government – but all other services were withheld or severely restricted.

Refuse wasn’t collected and drainage was virtually non-existent. Following the huge fire at the Shek Kip Mei squatter settlement on Christmas Day 1953, that left 53,000 homeless, the electricity company was allowed access to reduce the reliance on kerosene for cooking and lighting, but the service remained severely under-powered due to a lack of sub-stations in the area. Fresh drinking water was only available from a handful of standpipes, all located outside the City itself.

As the City grew, however, and the population rose to an estimated 20,000 by the end of the 1960s, it became clear that such an approach was unsustainable and from the mid-’60s onwards the Hong Kong authorities – working in association with the recently establish Kai Fong Residents Association – began operating in the City, tentatively at first but soon with an increasing confidence. An official government report from 1969 gives a clear account of the government’s involvement at that time:

POLICE

Police activity in the Walled City is the same as everywhere else except that certain licensing laws are not enforced. This is not satisfactory from the Police point of view but a change of approach may not be justified and, in any case, crime and vice are controlled. It is not considered that Police policy in the Walled City has any effect on the Police task elsewhere.

FIRE SERVICES

Normal action is taken regarding offences discovered as a result of fire, and legislation regarding the storage of dangerous goods is enforced. The Department takes all the normal measures to put fires out but does not carry out preventative measures. The most significant change since the 1960 recommendations has been the development of the Walled City from a fairly typical squatter are to one containing a considerable number of multi-storey buildings. Most of these are of sub-standard construction and lack any form of fire protection. The lack of access roads makes it impossible to get fire appliances close to many of the buildings.

URBAN SERVICES

The USD provides daily collection and removal of refuse and of nightsoil, maintenance of public latrines, removal of the dead, pest control, daily chlorination of the wells, investigation of infectious diseases. No food premises are licensed and no health legislation enforced. Residents are generally co-operative but the area nonetheless remains a potential focus of diseases whilst it lacks proper paved surfaces, drainage, piped water supply, ventilation and open space.

LABOUR

The Labour Department enforces legislation regarding the employment of women and young persons and undertakes periodical surveys of factories and industrial premises. Factories are tolerated which would not be allowed elsewhere. Closure orders have been made where there is a serious fire hazard but none have been enforced in recent years.

EDUCATION

The Education Department neither registers nor inspects regularly schools located within the Walled City, but it is prepared to act in any case where a blatant disregard for the safety of schoolchildren is brought to light. Sufficient primary school places exist in the immediate vicinity of Kowloon Walled City for children living within and without the Walled City.

RESETTLEMENT

The Resettlement Department does not conduct clearance operations within the Walled City and was instructed in July 1967 to suspend demolition of structures in the ‘sensitive zone’.

PUBLIC WORKS

The PWD’s Buildings Ordinance Office do not take action against illegal structures or extensions to existing buildings. Observations have shown that the methods of construction of many new buildings in the Walled City are rudimentary and quite unsafe (but) to exercise supervision over buildings would imply Government approval of that which is illegal.

HEALTH

The Medical & Health Department do not take action against the unregistered doctors or dentists who operate within the Walled City and are of the opinion that these should continue to be tolerated except in blatant cases involving risk to life.

BUILDING BOOM

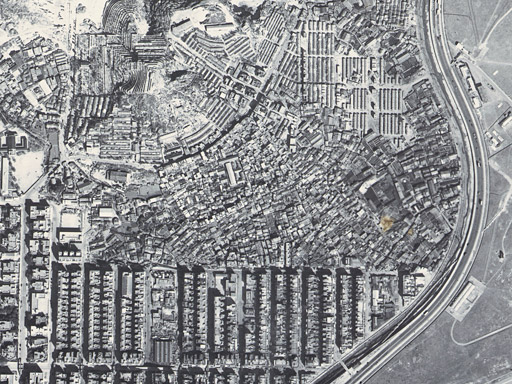

By 1961, as the map of that year above indicates, the ground floor area of the Walled City was fast reaching saturation point. There were a few open spaces, but the agglomeration of buildings into tight clusters separated by narrow alleys (the latter already settling into the recognisable street layout of the City’s final years) was now firmly established. By this time, most of the buildings had risen to three or four storeys in height, matching those in the surrounding Sai Tua Tsuen squatter settlement, but demand for accommodation within the City’s confines continued to grow.

There had been so-called developers operating in the City from the beginning of the 1950s, usually small private contractors who would enter into an agreement with an established building owner to redevelop their one- or two-storey dwelling into something taller, larger and generally better built. The original owner would take possession of the same number of floors he had had before, while the contractor sold off the extra floors for a quick profit.

It was a model that proved remarkably successful and by the end of the 1950s nearly all of the City’s buildings had been redeveloped in this way. In the early years, most builders had been cautious not to overstep a line beyond which the Hong Kong authorities might be forced to act. The City’s ‘special’ status had by then been firmly established, but just how far the residents, both law-abiding and otherwise, might be able to go had never been made clear. It was a constant game of cat and mouse, with those living and working there constantly pushing the boundaries to see what they could get away with.

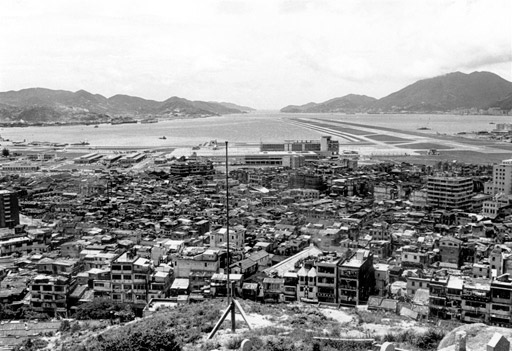

By the end of the 1950s and into the early 1960s, how much they could get away with was clearly quite a lot. As the 1962 photograph below indicates, taken from the hill to the north of the City, there were already several buildings straying up to five storeys and beyond, but the real breakthrough came the following year, as the Hong Kong Standard of 11th January 1963 reported under the headline ‘Big Building Boom Is On’, when a few brave individuals decided to build much higher.

The Hong Kong Standard article noted: “The Walled City of Kowloon is having a face-lift and private developers are busily pulling down old single-storeyed buildings and putting up new ones – most of them nine-storeys high. The redevelopment of real estate in the six-acre rectangular piece of land is booming. It is a striking contrast to the slackening of building industry in the rest of Hong Kong. Trade sources say that no less than a dozen sites are now being redeveloped by a handful of small-scale private contractors who know the place well. But flats in the newly reconstructed buildings are not cheap. They are selling at about $10,000 per flat with an internal area of around 200 square feet.”

And by all accounts the buildings were well appointed, the Standard’s report continuing: “The new buildings are equipped with modern facilities like water closets and running water … Electrical and telephone services are also available … The master-mind of all the buildings is a skilled worker. He is paid $600 a month and is in charge of all operations. ‘These buildings are safe, as all pillars are built with reinforced concrete,’ one master-mind says, ‘and the floors are four inches thick of reinforced concrete, a standard for tenements in new buildings throughout Hong Kong,’ he adds.”

As more and more buildings were completed over the next couple of years, without a response of any kind from the authorities, the floodgates opened and by 1968, when the photograph below was taken it is clear that nearly all the buildings had been redeveloped, not always to what seems to have become the nine-storey standard, but the inexorable rise of the City was clearly well under way.

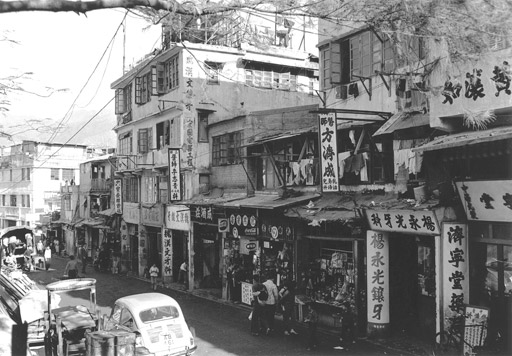

Looking east along Tung Tau Tsuen Road in 1963.

The junction of Tung Tsing Road and Tung Tau Tsuen Road in 1968.

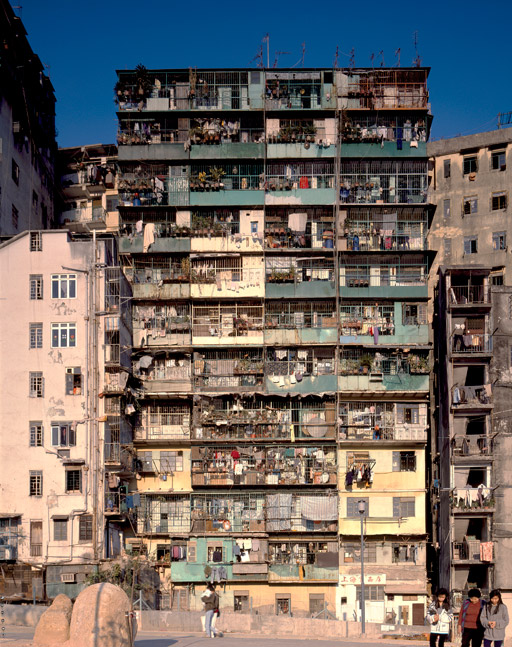

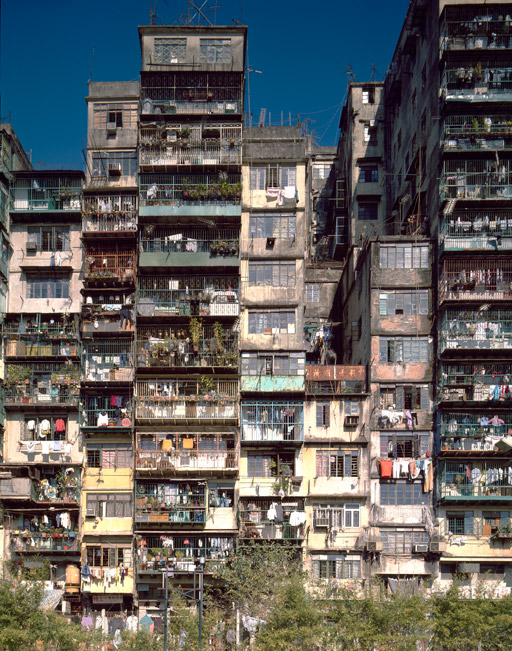

CAGED BALCONIES

One of the great contributions to the richness of Hong Kong’s urban scene were without doubt the caged balconies that lined the elevations not only of the Walled City, but also of many of the city’s other older tenement buildings. Sadly now but a distant memory, since they were classified as illegal structures in the late 1990s and torn down, these practical and otherwise very necessary additions to life in a tiny apartment were a source of constant delight.

They also represented a rugged, no-nonsense approach to vernacular design that was very much a signature of Hong Kong life in year’s gone by, and displayed a similar facility for making structures that can still be seen today in the temporary bamboo buildings or localised areas of scaffolding that can still be found from time to time, though these too are fast disappearing.

As I say, caged balconies were not unique to the Walled City, but in their very profusion there they had been raised almost to an artform that proved irresistible to the architectural photographer in me. I photographed them regularly and include just a small selection here, while others can be seen in the selection of prints available to buy.

On a purely technical note, I should point out that all of these images were taken on a land camera, resulting in 4” x 5” transparencies of incredible precision and clarity. Taking photographs on such a camera is a world away from the casual overindulgence of images available to the digital photographer. Instead, setting up a photograph via the inverted image projected on to the glass screen at the back of the camera – itself firmly anchored to a heavy tripod – forced you to look closely at what you were trying photograph.

Choosing the correct lens and framing the image just so, made possible by the camera’s high degree of movement between lens and picture plane, took time and patience. Spending half an hour to capture a single image is not unusual. Some photographers take far longer. Moving the camera a little to the left or the right, a little closer or a little further back, adjusting the rise and angle of the lens – every decision has a significant impact on the final image.

It requires an almost zen-like level of concentration, being totally involved in the moment, which I always found incredibly satisfying. Indeed, I still take the camera out occasionally now, just for the sheer pleasure of taking a photograph with it. I wasn’t planning it, but it has resulted in a remarkable series of images that I am grateful I had the good sense to take at the time and keep safe in they years since. I only wish I had taken more.

IN THE BEGINNING

For anyone who has spent any time in Hong Kong, or indeed in South-east Asia in general, the rate of growth and change in this part of the world is readily understood, but even so it comes as a surprise when looking at the aerial photograph of the Walled City above, taken in April 1949, to realise just how little was there at that time. Interestingly, even though the Japanese had demolished the walls during the War, the outline of where they once stood is still clearly visible, as are the central yamen buildings and the original school buildings to their left, though the latter would soon be torn down with their constituent parts used to build huts and smaller buildings more suitable to the needs of the refugees flooding into the area.

And flooding in they certainly were. The numbers are revealing. By the end of 1947 it is generally assumed that the population of Hong Kong, which had fallen to around 500,000 by the end of the War, had risen back to its pre-war level of just under one million, a mixture of returning residents and early refugees from the civil war in China. With so many buildings demolished or severely damaged during the conflict, however, there was even then a drastic shortage of habitable properties and significant numbers of squatter settlements were already beginning to spring up all over the hinterland of the Kowloon peninsula and on the hillsides of Hong Kong island.

But this was just the start. With the fighting in China increasing through 1948 and into the early part of 1949, as Mao Tse Tung completed his long march towards Beijing and power, a further one million refugees streamed across the border into Hong Kong, more than doubling the city’s population in just two years. And it didn’t stop there, with another million arriving during the 1950s. In the general austerity of the time, Hong Kong could barely cope, the only sensible solution being to allow the squatter settlements to grow at an inexorable rate throughout the 1950s and well into the 1960s.

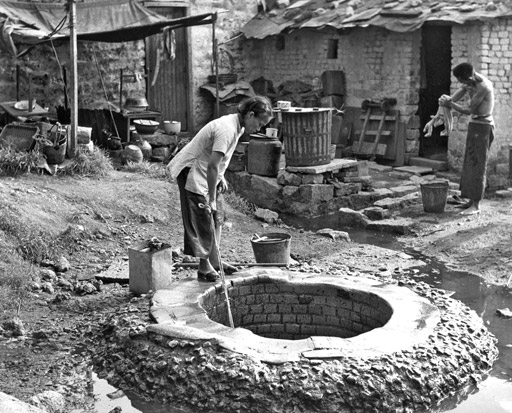

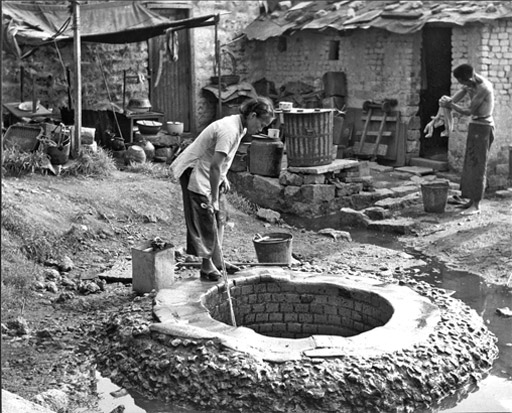

It is interesting to note in the 1949 aerial photograph that work was already well advanced on building the new Kowloon City around the grid of streets to the south of the Walled City, but elsewhere squatters’ shacks and buildings are already proliferating, though still interspersed with numerous fields and other open areas, even within the area of the Walled City itself. Sadly, no photographs of the Walled City seem to exist from this period. A photograph of a well, captioned as taken in or around Kowloon City in 1950 by the talented self-taught photographer Mak Fung, and another by him of children at a standpipe give a flavour of what life was like for those living in the squatter settlements of the time.

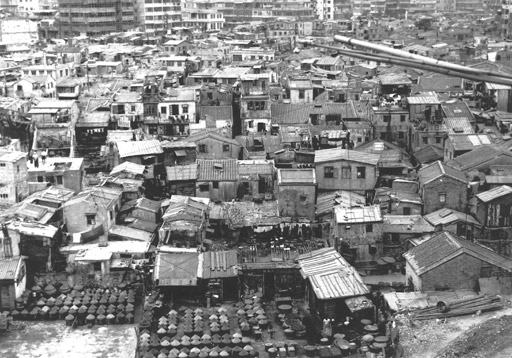

But the fields and open areas as shown in Mak Fung’s photographs were not to last long and, as shown in the 1956 aerial photograph below, the area was soon almost totally built up, a mixture of new developments and newly introduced public housing estates, and the growing number of self-built buildings within the Walled City itself and in the surrounding Sai Tau Tsuen squatter settlement. At this stage there was little difference between the buildings within the Walled City and the squatter settlement, most rising to just two, three or occasionally four storeys, though as the 1961 photograph of Sai Tau Tsuen shows (where a strict height limit was enforced) most, even at this stage, were substantial buildings with solid brick and concrete walls and tiled roofs.

But within the Walled City, this was about to change – the period of real growth was just about to begin.

An aerial view of the Walled City and surrounding area in 1956, just six years on from the photograph above but already heavily developed.

The Sai Tau Tsuen squatter settlement in 1961, like the Walled City crammed tight with substantial buildings.

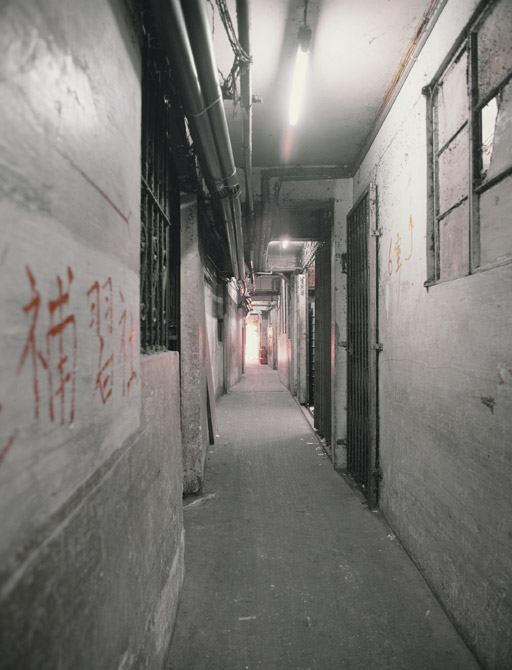

DARK ALLEYS

For some four years or so, between 1987 and 1991 when the City was still fully occupied, Greg Girard and I spent innumerable days in the City recording its architectural fabric and spaces as well as many of the people who lived and worked there.

Internal circulation was minimal, with just four alleys that offered anything like a direct link between Tung Tau Tsuen Road on the City’s northern boundary and Lung Chun Road (actually a pedestrian footpath) that ran along the City’s southern edge. None of these were straightforward thoroughfares: all twisted and turned to varying degrees as they passed between the ever encroaching buildings, as well as stepping down at regular intervals to take in the three storey or so drop in the site from north to south.

For the most part, the main alleys were well-lit and were kept clean and tidy, but step off these main routes into the many smaller side alleys and conditions deteriorated rapidly – light levels fell, sometimes to almost complete darkness, and nearly all were lined above with water pipes that dripped constantly on the uneven ground, making the going treacherous.

In certain places these side alleys became a veritable maze as they interlinked and stepped around buildings and, without any discernible landmarks or distant views, it was all too easy to become totally disorientated. You just had to stumble on until, hopefully, you popped out again onto one of the main thoroughfares, the direction of their slope offering a handy way of finding a way out – up the hill northwards to Tung Tau Tsuen Road and down towards Lung Chun Road and the neighbouring park to the south.

Every trip was an adventure and you would never know for sure what you would find. Even long-term residents were wary of stepping off into unknown parts of the City, most preferring to stick to the alleys they knew best – usually the most direct route between their place of residence or work and the outside world. And surprisingly, considering just how many people lived in the City, the alleys never felt that busy, even during the morning or afternoon rush. Indeed, on the smaller side alleys and up the many stairways, you could go for quite long periods of time without meeting another soul. It was just another of the City’s many mysteries.