A CHOICE OF EDITIONS

IMPORTANT NOTICE

It is now approaching 10 years since City of Darkness Revisited was first published and in that time your support has seen the original print-run – plus three separate reprints – continue to sell well. Our thanks to everyone who has made this possible.

Over that time we have managed to retain the original retail price to £58.50, but sadly ever-increasing production and delivery costs mean a modest rise in price is now inevitable. A new price of £64.00 per copy will come into effect when the fourth reprint becomes available in mid-March.

Complicating matters, due to an unexpected rush of orders in the two months before Christmas, copies of the most recent reprint are now out of stock, but we will continue to accept orders at the original price of £58.50 until the new copies arrive. This will mean a delay in dispatching copies, but all orders will be sent out as soon as the new reprint arrives. Regular newsletters will be sent to all those who order in advance to keep you up to date on progress.

Please scroll down to learn more about the two editions and visit the ‘Order a Book’ page to place an order. Again, our thanks.

THE STANDARD EDITION

Bringing this book to fruition was certainly an extraordinary journey and one that took far longer than we expected or intended. But having set ourselves the challenge of producing the best possible book about the Walled City, it was difficult to know when to stop. When we set out we thought a book of around 300 pages would be more than enough. In the end it ran to over 350 and in all honesty could easily have expanded to 400 or more.

There are a dozen or so more photographs that I would have liked to include and I am sure there is still a lot more about the City’s history to be uncovered. Right until the book went to print, we were still meeting people that we would liked to have interviewed, although we never did manage to track down any of those we photographed in the first edition, to find out where they are now – something we would have very much liked to achieve.

We could, for example, have easily spent another two or three weeks at the Public Records Office going through all files held there pertaining to the Walled City. we perhaps trawled through around a quarter of them – all those that seemed the most interesting from the short summary provided in the catalogue – and there were gems to be found in every one. There is certainly more to be found there, but that is for others to discover.

For now, I am happy to show off the book Greg and I, not forgetting our wonderful designer Susan Scott, have managed to produce in this new edition. As explained elsewhere, the book includes, as well as many interviews from the original edition, a number of new essays and numerous new images on topics not covered before: whether about the City’s architectural development in the 40 or so short years of its existence; the truth behind its many myths as ‘a den of iniquity’; the politics that allowed it to develop in the way that it did; and how it has been transformed through the power of popular culture, both in Hong Kong and around the world.

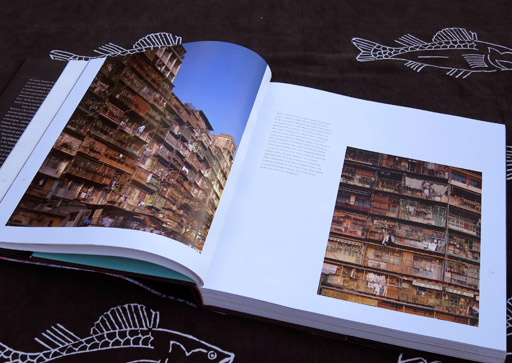

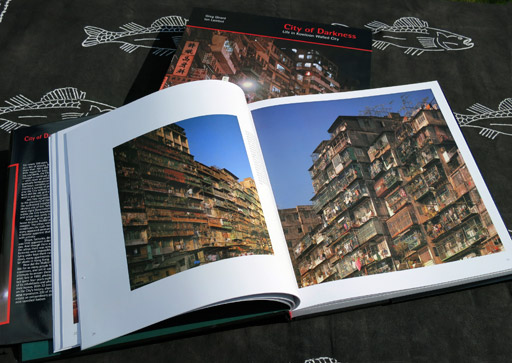

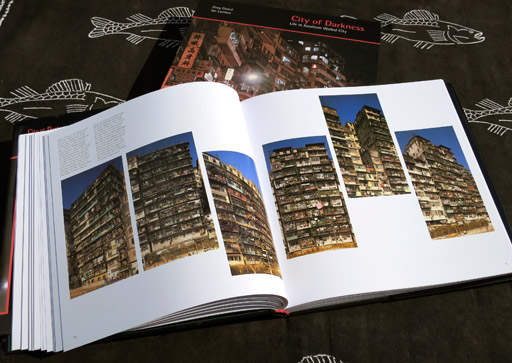

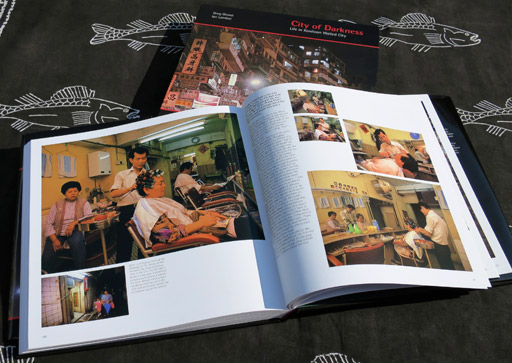

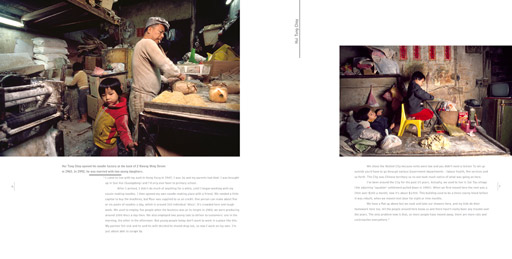

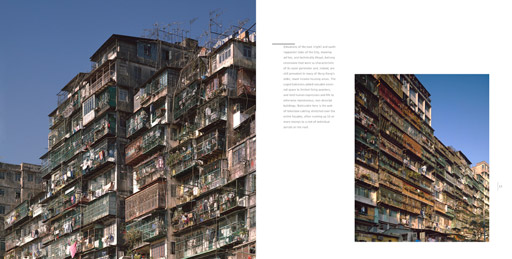

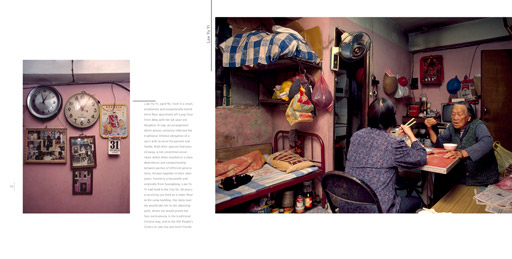

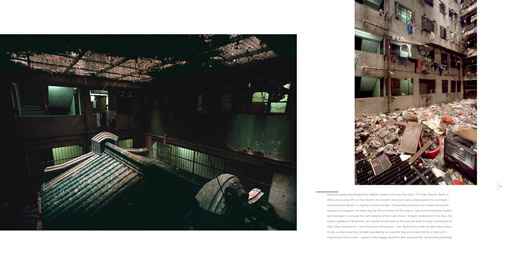

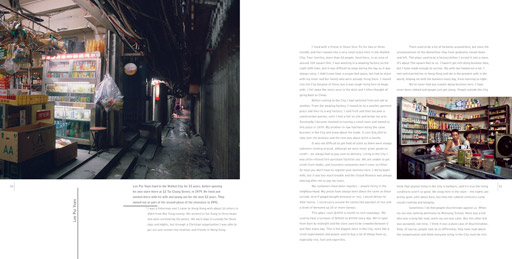

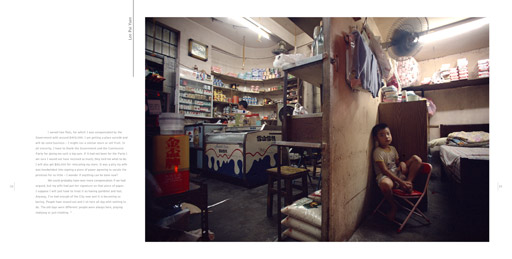

I include below a display of typical spreads to illustrate far better than I can in words how the new book looks and feels.

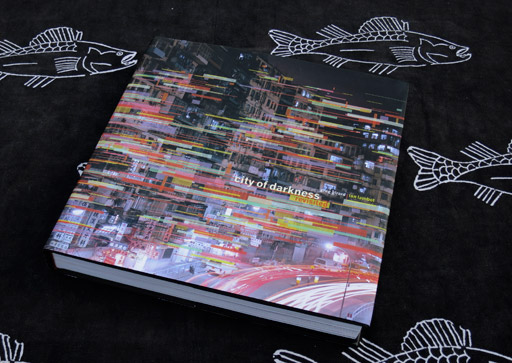

The Standard Edition has 356 pages – at a trimmed page size of 270 x 273mm – and contains over 320 photographs, nearly all in colour. The book is hardbound and is delivered in a printed card slipcase.

The book can be ordered now at the current retail price of £64.00 (for the UK) or more for other parts of the world. All prices include postage. Please refer to the ‘Order a Book’ page for details.

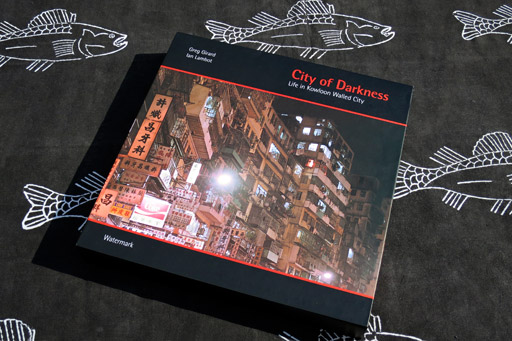

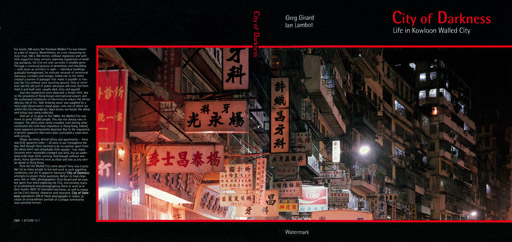

CITY OF DARKNESS – SPECIAL REPRINT

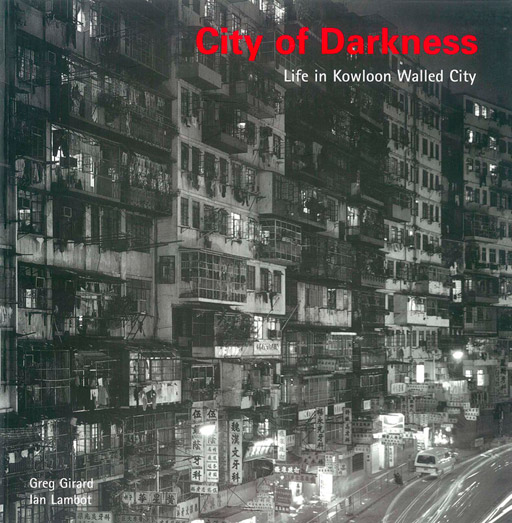

The original edition of the book, City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City, served us remarkably well for close on 20 years, transforming from hardback to softback and being reprinted multiple times, always from the printer’s films produced when the book was first published in 1993. Every copy of the original edition came from that one set of films.

The deluxe Special Reprint edition, signed and including one of the original page films, is now sold out. However, we still have a limited number of unsigned copies of the book, including slipcase, available at the reduced price of £120.00 including UK postage, or £140.00 to Europe and £160.00 to the rest of the world. Please go to the ‘Order a Book’ page for further details.

THE BOOK REVIEWED

We were fortunate throughout the book’s production, and especially during the Kickstarter campaign, to receive a good deal of media coverage, either in print or via internet editions and programmes. In the latter camp, the Asia Wall Street Journal was helpful, while coverage on CNN provided the Kickstarter campaign with a huge boost, for which both Greg and I are eternally grateful.

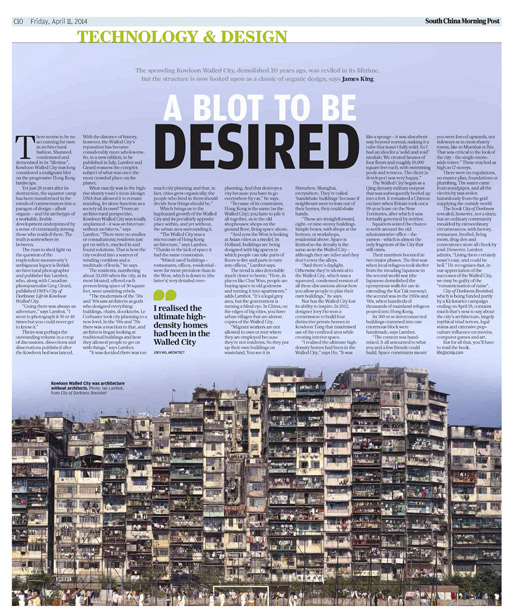

The internet, of course, was essential in providing the much needed international exposure, but it was primarily the print media that helped spread the word in Hong Kong and around the region. Shown here are cuttings from the South China Morning Post, Time Out Hong Kong and the Ming Pao newspaper, but there were also articles in several other magazines

Now the book has been published, the emphasis is shifting towards reviews. It is always a bit of a lottery for us smaller publishers whether we will make the cut when it comes to getting a review in one of the more prestigious magazines, so we are especially grateful to Mark Clifford who has produced, for the Asian Review of Books, this first review of City of Darkness Revisited. Mark is the author of the forthcoming The Greening of Asia (Columbia University Press, 2015) as well as the executive director of the Asia Business Council. Our thanks to Mark, whose review we include here in full.

“When it heaved with life, the Kowloon Walled City was notorious. The enclave, protected by a historical quirk from British rule in Hong Kong, embodied a tangle of fears in the collective consciousness – it was a place of opium and whoredom, lawlessness and murder. It epitomised crime and overcrowding, triads amidst the tenements, chaos in the midst of civilisation.

Two decades after its destruction, the Walled City has acquired an increasingly shiny gloss of respectability. Architects of the new urbanism celebrate its dense, human, organic development. The government’s dystopian view of the Walled City as a place of “notorious… drug divans, criminal hide-outs, vice dens and even [sic] cheap unlicensed dentists,” has given way to a vision of the Walled City in the collective imagination as the lost paradise, a sort of Atlantis, Xanadu and urban Shangri-La rolled into one.

Symbolising this re-imagined city, and helping make the gloss even shinier, is a new and dramatically expanded twentieth-anniversary edition of City of Darkness. In its earlier editions, the book was something of a cult classic. It was also a book that focused very much on the people of the City, trying to de-mystify and humanise this place of urban myth.

The new edition is big and bold, a colourful heavyweight book perfectly suited for gift-giving and coffee-table viewing by people who never would have gone to the City while it was real. But it is also a far more ambitious attempt to look at the underside of the city and at its larger global and urban-architectural dimensions.

The sometimes tight, cramped look of the original has been replaced by larger photos. A number of new essays bring more depth and richness to the book. Fionnuala McHugh’s essay on the politics of the Walled City clearance sheds light on a secretive chapter in Sino-British relations that until now has remained untold. There is also additional material on the unique architecture and the global influence that the Walled City has come to exercise, especially in the years since it was torn down.

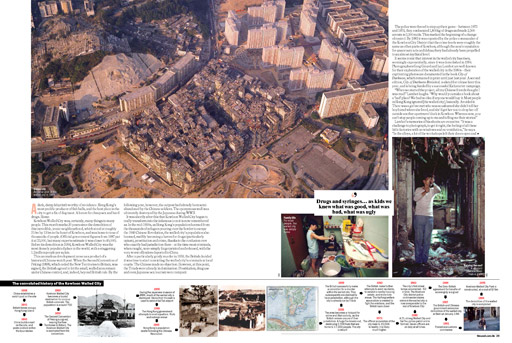

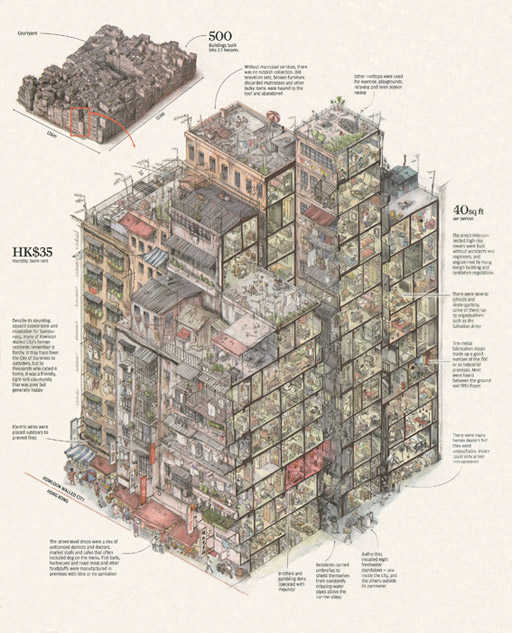

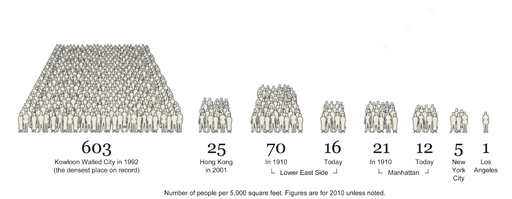

The density of the 14-storey Walled City was unequalled anywhere: if Manhattan were built to the same density it would be home, not to 1.6 million people, but to 65 million. Most informal settlements spread out, but the Walled City was forced to go up, limited to the footprint outlined by the grounds of a former Chinese military compound that was, as the result of a historical quirk, not subject to formal British rule. As recently as the 1960s, pig pens and garden plots had been a feature of the settlement, but the city’s growth and its hunger for space – space for living, for working, for praying, for eating – saw the City caught up in the race to build Hong Kong. The City only topped out when the government forced the demolition of the top storeys of a building that breached the 150-foot height limit imposed because of the proximity to Kai Tak Airport.

This lavishly-illustrated book centres on Greg Girard’s [and Ian Lambot’s] striking photos. But the volume ranges broadly over the past 150 years. A detailed 1865 photo of the old fort, surrounded by hills and rice paddies, and a number of other striking historical photos trace the City’s development.

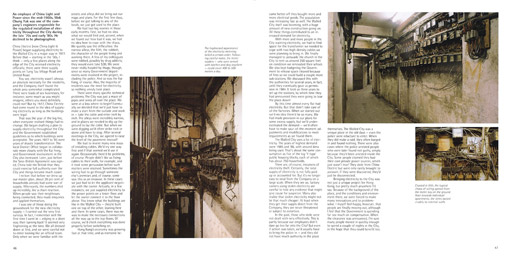

A summary history details the repeated thwarting of British attempts to impose state control on the 0.01 square-mile home to 35,000 people. In pragmatic accommodation to reality, electricity, postal and water service were all provided, despite the lack of formal legal jurisdiction. This was a space that existed in a permanent state of ambiguity and yet had to deal with the reality of two tonnes of garbage a day, all of which adds richness to interesting vignettes by, among many others, a postman and a China Light & Power engineer who discuss the daily reality of working in the Walled City.

The Walled City’s state of organic anarchism was summed up by author William Gibson: “[T]here was no law there. An outlaw place. And more and more people crowded in; they built it up, higher. No rules, just building, just people living. Police wouldn’t go there. Drugs and whores and gambling. But people living, too. Factories, restaurants. A city.” This is a fascinating, rich book. It is one that can be casually flipped through but it is, above all, a rich and deep work that benefits from repeated reading.

Anyone who loves Hong Kong’s grittiness will enjoy this book, for it is all here. The triads and the illegal dentists, the cops and the junkies, the racing-pigeon breeder and the noodle-maker, the mah-jong players and the metal-working factories. As Ian Lambot writes of the original impetus behind the project that he and Greg Girard first conceived of more than 20 years ago: “[I]n a way, the City stood as a microcosm of Hong Kong – just ordinary people trying to get by in the best way they could.”

Few books capture ordinary people in an extraordinary city as richly and lovingly as does City of Darkness Revisited.”

A CITY CLEARED

It may come as a surprise, but the Hong Kong authorities had tried to clear the Walled City, or parts of it, several times before the successful plan for its demolition was finally implemented. The full story of these earlier attempts, and why they had failed, will be included in the new book, in an extended article written by the respected Hong Kong-based writer and journalist, Fionnuala McHugh.

You will have to wait for the book to come out, to read that part of the story, but here is an excerpt explaining how that plan for the final clearance and demolition actually came about. It is a story of secrecy and subtle diplomacy that is only now, 20 years later, beginning to come to light. It is explained here in some detail for the very first time.

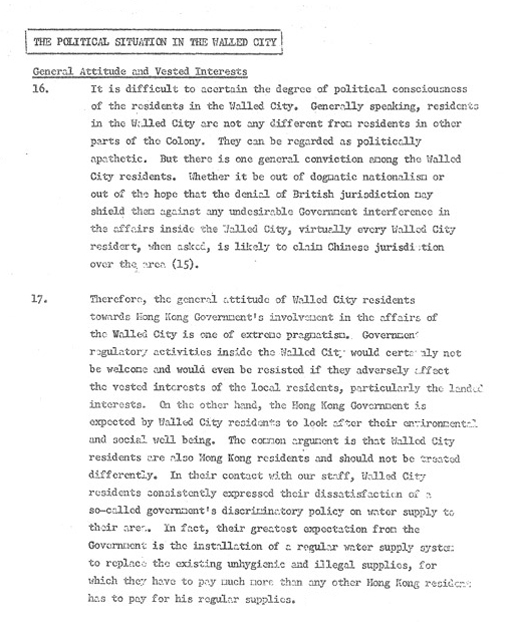

“On 14 April 1986, Donald Tsang, who was then the Deputy Secretary in the General Duties Branch (and would, many years later, become the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’s second Chief Executive), organised a meeting with Gordon Jones [District Officer for Kowloon City] and Richard Margolis, the Deputy Political Adviser. He told the men that the Governor, Sir Edward Youde, wanted to clear the Walled City. There was now enough housing stock in the area to resettle the residents but, perhaps more to the point, there was concern that the appalling conditions there might provide convenient post-handover propaganda with which China could denigrate the British administration. Its continued existence also posed very serious risks of fire and to health that really needed to be resolved. So a paper was to be prepared on a potential clearance operation: Jones would look at the logistics side, Margolis at the political dimension. After analysis and tweaking in Hong Kong, it would be sent to Beijing for further discussion with the Chinese Government.

It was essential to maintain total secrecy, in the short term because they wanted no news of the operation leaking to the press before China had been consulted and, of course, in the longer term because this would have caused an influx of squatters into the Walled City hoping to claim rehousing benefits and compensation. Consequently, apart from Jones, the only other person in the Kowloon City District Office (KCDO) who knew what was happening was his personal secretary and, for their part at least, they ensured that any future communications between the KCDO and other parties in the Government on the subject would be done through correspondence classified as ‘Confidential’ rather than ‘Secret’, as the latter (an unusual classification for a KCDO matter) would only have raised suspicions that the documents must have something to do with the Walled City. As Jones had been told that China’s leader Deng Xiaoping had a particular interest in sanitary matters, he also instructed a young executive officer to take photographs of the Walled City’s lavatories, though he had no idea of his mission’s relevance.

Remarkably, considering the matter’s complexity and delicate nature (but also aware that time was of the essence), the paper was completed within a few days and the following week, on 21 April 1986, a meeting chaired by Sir Edward was held in Government House, where it was agreed that the clearance would proceed. To an outside observer with knowledge of the painful past, such intense preparation for an operation, which would certainly be costly and inconvenient, and might well be a well-publicised, violent failure, is baffling. “This might sound corny”, said Margolis, in an interview 26 years later, “but there was an extraordinary degree of pride in what the colonial administration had done here, and a very powerful desire to leave Hong Kong in good shape. The temptation to say, ‘Here’s an eyesore you [China] helped to perpetuate, so why don’t you deal with it?’ never really crossed anyone’s mind.”

Delicacy of touch was the keynote.“We had settled the 1997 issue but there was this tiny, little residual problem,” as Margolis put it. “We had to couch it fairly carefully because we didn’t want to go too far in inviting the Chinese government into decision-taking over all these people. What we were after was for China, in the event of the inhabitants protesting to them, to make it quite clear to them that this was a matter for the Hong Kong administration. Then people would get the message the game was up.”

China gave the nod. In a 2011 Chinese television documentary, Qiao Zonghuai – former vice-minister at China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and former deputy-manager of Xinhua’s Hong Kong branch – recalled his involvement in those negotiations. At an informal diplomatic banquet in 1985, a British government official had mentioned to him a pre-handover plan for the Walled City. “This is not a matter that you propose off the cuff,” said Qiao. “At first I was pretty surprised, I felt that it was rather sudden. You cannot imagine the sensitivity . . . In hindsight, making his proposals on such an occasion was partly calculation.”

Qiao was initially inclined to take a hard line but he also recognised that since the signing of the Sino-British agreement the old, knee-jerk response had altered. Now, it was diplomacy that kicked in. However arbitrarily the notion had been raised, British hints at demolition and relocation for urban improvement seemed reasonable. He reported the conversation to his superiors in both Xinhua and the Sino-British Joint Liaison Group, of which he was a member.

Two days later, Xinhua senior officials summoned Qiao to a late-night meeting in Hong Kong. As usual (“Our telephones were tapped”), he wasn’t told the agenda in advance. Only after he arrived was he asked to explain the situation to his colleagues. One of them, who’d been familiar with the Walled City since the 1950s, reacted with intense emotion. “Normally, he was a jovial fellow, he described himself as Boss of the Kowloon Walled City,” said Qiao. To this man, however, allowing the British to oversee anything in the City – even demolition – would bring into question Chinese rights of sovereignty and government. Why, he asked, couldn’t China wait until 1997?

Qiao’s answer was pragmatic. “If we made a mess of it,” he said, “the masses might have gone out on the streets and demonstrated and this could have led to local rioting.” Ever since the banquet, he’d been racking his brains to work out what the British were up to. He decided that what they wanted, each time they left their colonies, was a glorious withdrawal; and in order to make an imposing exit, no “grotty, dirty areas” could be left behind. In his reports, Qiao wrote that the British had always felt they had the right, and the ability, to rule over the Walled City but they’d never had the will to do so because of Chinese opposition. Now, it was to the benefit of both sides that this should change.”

THE NEW EDITION

Thoughts of producing an all-new edition of our book about life in Kowloon Walled City first emerged towards the end of 2011. It has been a source of constant surprise to us that interest in the Walled City has continued to flourish over the years. Books of this kind appear, sometimes to considerable acclaim, but inevitably time moves on and even the best may slip out of print, often within a few years.

But not so City of Darkness. When it was first published in 1993, in a small print run of 1800, we had no idea whether it would sell. We hoped to cover our production costs, but for both of us the book had very much been a labour of love we were determined to publish at whatever the cost. Many of our Western friends were convinced it would sell, but among our Chinese friends the signs were far more equivocal. Just why would you make a book about such a bad place, they would ask.

And certainly in those first few years, our main sales base was Western residents and tourists in Hong Kong, backed by a loyal, though by no means large, band of interested designers and architects worldwide, who had either heard of the place or seen photographs of it in some magazine or other. Indeed, sending pictures out to newspapers and magazines was just about our only attempt at publicity. It is difficult to imagine now, but this was a world before the World Wide Web.

Happily, interest proved great enough to warrant a reprint after 18 months or so (another modest run of around 3000), which continued to sell in dwindling numbers for the next or year or so. And that, we thought, was that. Ian moved back to the UK in the interim, but on a return visit to Hong Kong at the end of 1998 – after the territory’s handover to China – he was surprised by the number of people approaching him to ask what had become of the book and whether they could buy a copy.

Intriguingly, many of those asking were Chinese friends and acquaintances whose interest in the Walled City, now that it no longer existed, had taken a new and unexpected turn. Thinking another reprint might be worthwhile, we began putting out feelers, in particular around Hong Kong’s architectural community which Ian knew well. And in a very short space of time we had elicited enough orders to ensure that a new printing – now in a softback edition with a cover designed by Evelyn Hwang, a good friend of Greg’s – would at the very least pay for itself.

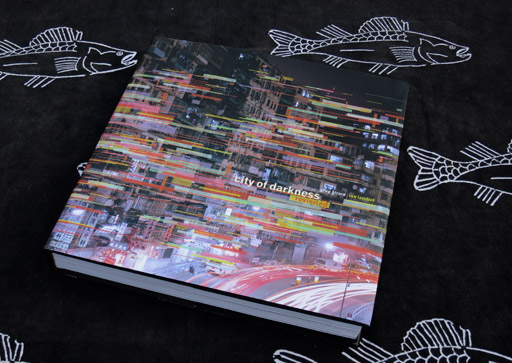

Evelyn Hwang’s cover for the softback edition of the original book.

And so, in February 1999, another 1800 copies went out to bookshops, after which the book remained in print until the end of 2012. Responding to the vagaries of the worldwide economy, sales fluctuated over the years, sometimes rising to more than 100 a month and at others falling to below 500 a year, to the point that we thought the book might have run its course. But then the orders would pick up again, and in recent years they have achieved not just earlier levels but have seen a noticeable rise in interest. Indeed, the final reprint in late 2011 surprised us by selling out far more quickly than we were expecting – hence, in part, the longer than intended break before the arrival of the new edition.

Realising that interest in the Walled City was only continuing to grow (as even a cursory search on the internet will attest) and aware that the 20th anniversary of both the City’s demolition and the original book’s publication was just over horizon, in 2013, the thought took hold that perhaps it was time to return to the Walled City and produce an entirely new edition, bringing the story up to date and filling in the gaps.

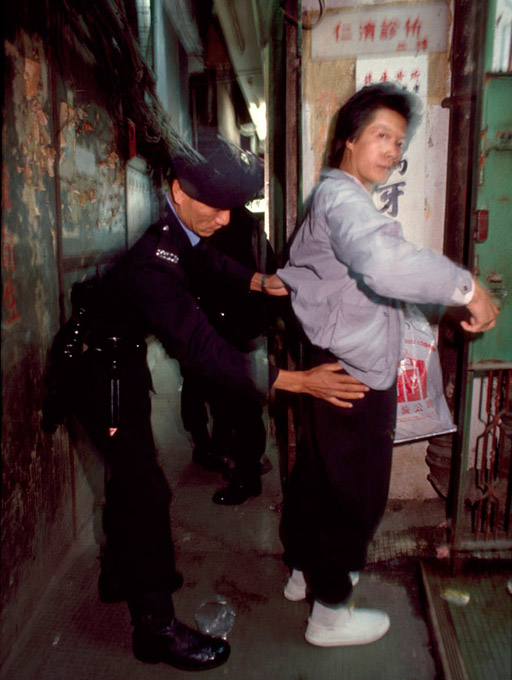

As explained elsewhere, the original edition, partly out of consideration for residents’ feelings and partly owing to lack of funds, deliberately concentrated on the lives of those living and working there. Contrary to popular belief, certainly the belief of most Hong Kong residents, Triad activity in the Walled City at that time was negligible – actually less than in some other parts of Hong Kong – but most residents were still looked down upon. The Triad connection was a highly sensitive subject among many of those we met and we chose not to confuse the issue by including extensive accounts of Triad activity or drug use.

Not that this would have been easy. Obtaining reliable facts and figures in the early 1990s proved to be very difficult. The police force had been completely overhauled after the introduction of the Independent Commission Against Corruption in 1974, but the endemic corruption that had infiltrated the force throughout the 1960s and early ’70s was not something people were willing to talk about. And it was assumed that any story about the Walled City was bound to dwell on that. Indeed, as we have since found out, it does to this day.

The new edition will include extended new sections on the history of the Triads in the City, the City’s peculiar legal status, its architecture, and how it is has become part of popular culture.

And finding out about the political situation was no easier. By its very nature the Civil Service is a secretive organisation and the administration of the City had long been a particularly thorny issue. The whole issue of the negotiations with the Chinese government that led to the City’s clearance and demolition was out of bounds, and the 20 years rule meant that most government papers that might have offered a few clues were unavailable as well, and would remain so for the foreseeable future.

Surprisingly, too, despite Ian’s architectural background, the story of the City’s architectural development also seemed secondary to the story of those that lived and worked there. It struck us it would have muddied the waters, with the danger that the book would be seen as a purely architectural one, which was not our intention at all. Happily, a good deal has changed in the past 20 years. A vast amount of new material has come to light and people on all sides, both former residents and those who were responsible for maintaining a degree of authority in the City were happy to talk.

And so, as well as many of the photographs and interviews found in the original edition, the new book will include several new sections: on the City’s architecture, how it grew and evolved over time, and on the City’s peculiar legal status under two jurisdictions but effectively administered by neither, and how this unique situation coloured every stage of the City’s development. Another essay will explore the myths and realities of the Triad’s activities there, and how the police tried their best to keep up with each new development. Contrary to one of the City’s most enduring myths, the police conducted daily foot patrols within the City virtually from day one – and usually in pairs, not in groups of 40 or more as another persistent myth would have us believe.

Finally, other essays will explore how perceptions of the Walled City have changed over time, from being shunned by most Hong Kong residents during its lifetime to now being seen, almost with pride, as part of the territory’s rich cultural heritage – while internationally it has been appropriated by numerous cultural and popular commentators as a tabula rasa onto which they can layer any number of meanings and arguments. The Walled City’s rich history just continues to grow.

The final design of the book is now coming together and the book will be going to print in April, with phased publication dates over the summer to allow for shipping and distribution to different parts of the world. Appropriately, the book will first appear in Hong Kong towards the end of May with further launches in Europe and the USA following in early July. It will be possible to pre-order books at a reduced rate Via a Kickstrater campaign which is due to be launched soon. Go to the ‘ORDER BOOK’ section for further information.

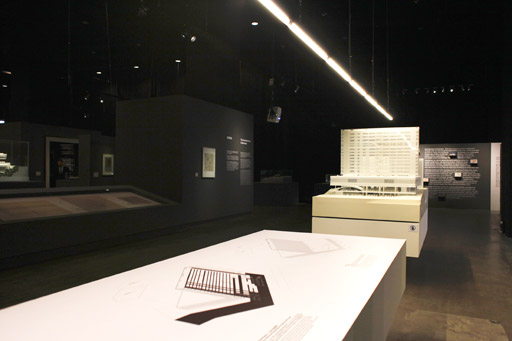

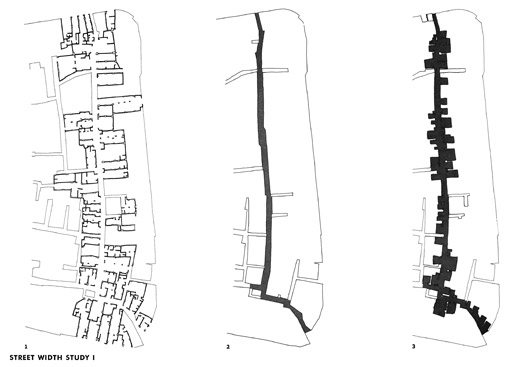

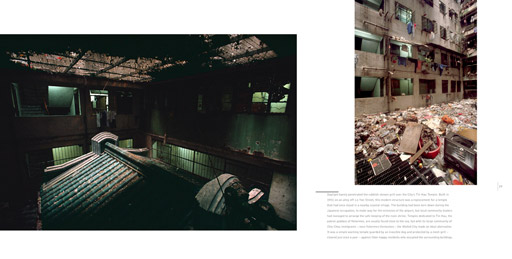

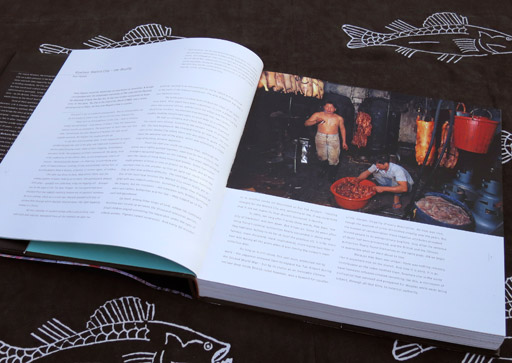

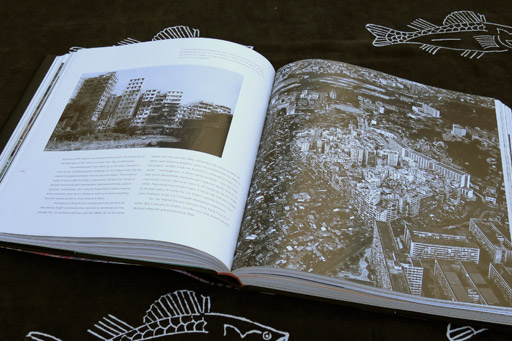

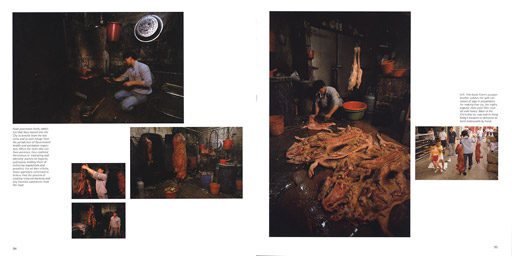

A sample spread from the new edition.

A NEW LOOK

The original edition of City of Darkness was designed by Ian Lambot in 1992, shortly after he had spent three years working with Otl Aicher on the design and production of the four-volume series of monographs on the work of Norman Foster and Foster Associates. As such, the book was inevitably coloured by Otl’s quite structured approach to book design.

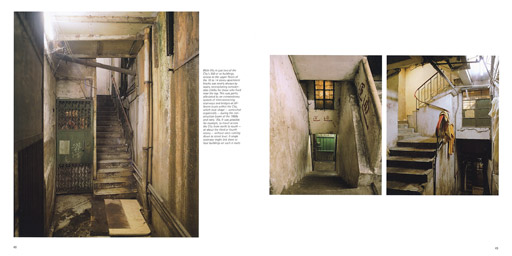

It was also inevitably influenced by the very real experience of spending time in the City, with its tight spaces and apparent lack of order. The texture of the layouts, in particular in the use of the photographs, was therefore quite dense. And as there was no real storyline to follow, everything was jumbled up, jumping from alley scenes to factory interiors to external views to personal interviews and then back again – much like life in the Walled City itself.

But time has moved on; the immediacy of our time in the Walled City has dissipated and both of us have been able to go back and sort through our photographs more dispassionately, with new eyes and clear minds. We wanted to keep the best of the interviews and inevitably – with the City long gone – many of the photographs will be the same. But in other ways, City of Darkness Revisited will be quite different. Both of us have come across images either omitted or used in a minor way that make us wonder now, what were we thinking? The new book will allow us to make amends, adding new images here and there, and giving due prominence to others previously hidden away.

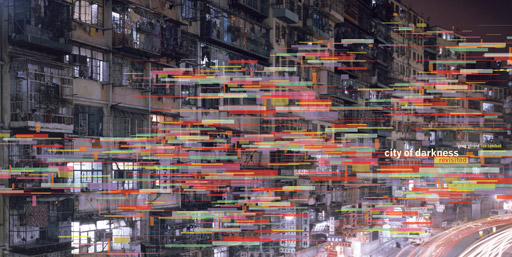

New images have been included and the emphasis placed on existing photographs has changed. And, of course, there is also a considerable amount of new material not included in the earlier book, not least a whole series of photographs of the City from the 1960s and’70s that have never been published before, as well a numerous new drawings of the City’s buildings and a broad range of images showing how the Walled City continues to influence popular culture –in the form of art, books, movies and computer games – to this day.

More importantly, we wanted to open up the book, so that the photographs could be appreciated for themselves, as truly evocative images of times past. A lot has changed in Hong Kong in the past 20 years and most aspects of life that we captured during our time in the Walled City – in isolation not unlike many other parts of Hong Kong then – have all but disappeared in the years since.

To help give the book a new look, we decided that it would make a good deal of sense to bring in an entirely fresh set of eyes, so the new book is being designed by the award-winning graphic designer Susan Scott, a friend of Ian’s born in the UK but now a long-time resident of Montreal, Canada. Go to Susan’s website at www.design514.com to find out more about her many accomplishments.

The layouts shown here are taken from a first draft of the book and should been seen as representative rather than a true reflection of the finished pages, though these will be updated regularly as more and more of the design is finalised.

GREG’S STORY

I first visited Hong Kong in 1974. I heard stories about the Kowloon Walled City on that visit but it wasn’t until I moved to Hong Kong years later that I saw the Walled City for myself. I came across it one night in 1986 when photographing near Hong Kong’s old international airport, Kai Tak. At that time the Walled City was partially surrounded by a two-story squatter village, and to enter the City you had to make your way past the hostile stares of village residents. At night the massive 12- and 14-storey facade glowed from the interior lighting of hundreds of apartments, and hummed to the sound of air conditioners and fans and television sets tuned to evening programmes.

Once inside the first thing you noticed was the tangled overhead electrical wiring and plastic water tubing, and the narrowness of the ‘streets’ – alleys formed in the spaces between buildings. Nothing I had heard about the place was any help to process the information my eyes, ears and nose were delivering. In modern Hong Kong this place was something from a parallel universe. I wasn’t able to make any photographs on that first visit, but soon returned and started trying to make sense of the place, gradually gaining the trust, or at least the indifference, of residents.

I was introduced to Ian during this time, intrigued to learn that someone else was interested in photographing the Walled City. And we ended up collaborating on the book City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City. In retrospect it seems astonishing that the Walled City didn’t attract more attention – from photographers, film-makers, architects – while it was still standing. And in our new book, City of Darkness Revisited, we go to some length to register the attention it has received and the influence it has generated since its demolition in 1993.

I am sometimes asked whether I think the Walled City should have been preserved. Years ago I usually said that it would have been impossible – preserving it would probably change it into something else or, if kept as it was, it would be unfair to expect people to tolerate those grim conditions. Recently though I’ve started to wonder where a conversation about it all might lead.

THE ORIGINAL

As explained below (see IAN’S STORY), the first ideas for a book about the Walled City began to percolate in my mind towards the end of 1987. I had started to build up a fairly impressive portfolio of architectural photographs by then, both of the exterior and the main alleys, but the more time I spent there the more I realised that the real story was not so much the architecture, extraordinary as that was, but the people who lived and worked there.

Just how many people actually lived in the City at its height is unknown, with estimates varying between 40,000 and 50,000. Greg and I tend towards the lower number, but even considering the 33,000 or so that were definitively recorded living and working there when the clearance was announced, this made it by far the most densely populated location the world has ever seen –outstripping by a considerable margin the lower east side of New York at the beginning of the 20th century, generally considered to be the most densely populated place before the emergence of the Walled City.

With the decision made that the book should include the people who lived there, the question then was how this might be achieved. By nature I am the archetypal architectural photographer, taking pictures traditionally devoid of people and working with available light, not a sensible option when trying to photograph people in the tight confines and gloom of the Walled City. Enter stage left, Greg Girard. It turned out a mutual friend knew both of us and knew Greg had been photographing in the Walled City as well.

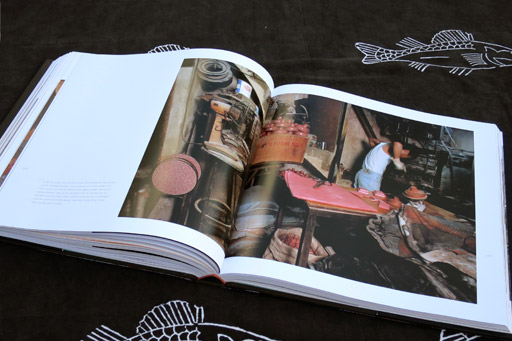

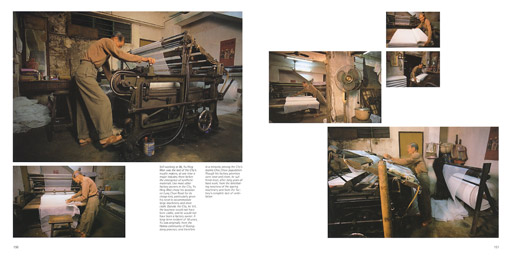

Greg was then working as a photojournalist with a particular interest in photographing people as naturally as possible. He had also worked out a way, using portable lighting and balancing ambient light, of photographing inside the Walled City under mixed light sources while retaining rich and well-balanced colour. This was the days of transparency film, when the possibility of manipulating the colour of photographs at a later date was very limited indeed.

To cut a long story short, a meeting between Greg and myself was quickly set up. Thankfully, we found we got on, each admiring the other’s particular skills as a photographer and, more importantly, I think we both realised that the combination of our images might make for a far richer book than anything we could produce individually.

The next question was how best to tell the people’s stories. Very quickly we decided that we wanted those we photographed and interviewed to be able to tell their stories in their own words. But for this to work we needed a local Chinese person not overly intimidated by the Walled City’s fearsome reputation, who would be able to build relationships with people that would allow them to talk openly. By chance I had connections with Hong Kong University and someone there suggested that I talk to Elizabeth Sinn who was working in the History Department there and was then actively involved in running an oral history programme.

And so, in the summer of 1988, when we knew there would be a number of students seeking employment, I explained our plight to her, and without hesitation she suggested we speak to a fresh young graduate who had been closely involved in the oral history programme and was, by her estimation, an almost perfect fit. And so it was that Greg and I first met Emmy Lung, who was to become an integral member of the Walled City team.

Though small in stature and with, on first impressions at least, a quiet character, Emmy proved both fearless – soon exploring the City quite happily on her own – and inordinately inquisitive, happy to talk to anyone she met of any age or background and quickly gaining their trust. It proved an invaluable skill and over the following 18 months or so, either following up on contacts either Greg or I had made or working on her own initiative, she managed to compile a range of interviews from a broad spectrum of those living and working in the City.

To a large extent we tended to work independently, each of us fitting in our visits to the City around other commitments. And, in the early stages at least, we had no real plan, each of us reacting solely to what we came across on our visits there. As time went on, however, it became apparent that a more structured approach was necessary if we were going to build a balanced picture of those who lived and worked in the City.

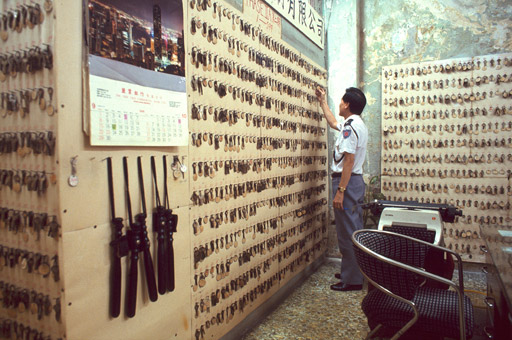

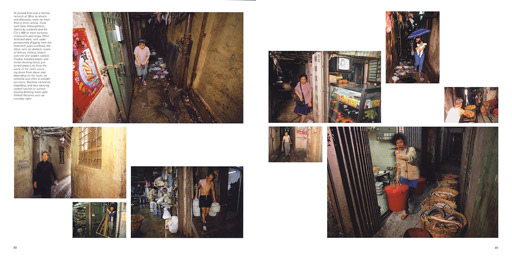

To a certain extent, the very nature of the City allowed us access to places normally hidden behind closed doors. In the City, where any feeling of greater space and ventilation was always appreciated, doors tended to be left open. The distinction between public and private space, particularly in the alleys, was far more blurred than usual and it was quite easy for us to wander into factories, workshops and even dentists’ and doctors’ clinics and ask if we could take pictures of or talk to the people there. Very few people said no and, indeed, over time our presence in the City became quite well known, allowing us access to yet more doors and possibilities.

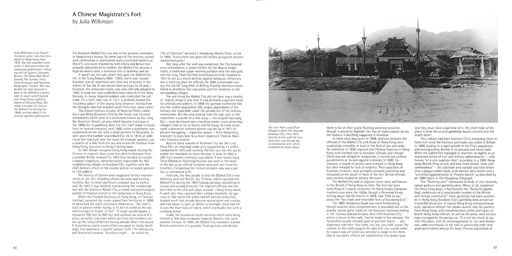

And so, slowly, the book evolved. Other writers came on board, most notably Charlie Goddard with whom I shared an office at the time, to fill in some of the background stories – about the electricity and water supplies, for example, and the clearance, while Peter Popham supplied an introduction (see AN INTRODUCTION) and Julia Wilkinson described the City’s earlier history as a magistrate’s fort. Always though, the main focus was on the ordinary people who lived and worked there.

To a large extent, aspects of the City’s dark past, the infiltration of the Triads and the drug dealing, as well as a detailed explanation of the City’s complicated political structure was avoided. We concentrated on recording how the City appeared to us during the four years or so we spent there, when the City was still fully occupied between early 1988 to late 1991. In the past 20 years a great deal of information on these other aspects of the Walled City story has come to light, but all that will be explained in the new edition.

AN INTRODUCTION

With the original edition now out of print and unlikely to be resurrected (apart possibly from a specially produced limited edition, but more on that elsewhere), there was a danger that Peter Popham’s beautifully elegiac introduction to that edition might disappear. This would be a shame as it is, perhaps, the best written description of what it was like to encounter and walk through the Walled City in its heyday. A long-time resident of Japan with a strong interest in the built environment, his early feature articles appeared in numerous newspapers and magazines around the world, while his interest in the genesis of Japan’s urban architecture culminated in his book ‘Tokyo: City at the End of the World’ (Kodansha, 1985). For the past 25 years he has been a feature writer and foreign correspondent without portfolio at the The Independent newspaper in the UK.

Peter has kindly agreed to write the introduction for the new edition, which no doubt will appear on this website in due course, but without further ado here is his introduction from the original edition.

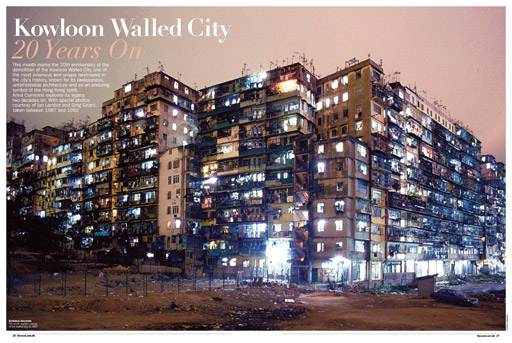

“Hak Nam, City of Darkness, the old Walled City of Kowloon has come down. Many people in Hong Kong, both Chinese and foreign, for whom it was never more than a disgusting rumour, believed it went years ago. Not so. Almost to the end it retained its seedy magnificence. It had never looked more impudent, more desperate, more evil to some eyes, more weirdly beautiful to others.

For many years its limits were blurred by a dense undergrowth of squatters’ shacks that spread outward from it. As the first step towards clearing the whole site, these were swept away and replaced on two of the City’s four sides by a dusty park where the landscaping is only now taking hold. The City now reared up abruptly from the bare ground, 10, 12 and in some places as many as 14 storeys high, and there was no mistaking it: six-and-a-half acres of solid building, home to some 33,000 people, not the largest, perhaps, but certainly one of the densest urban slums in the world. It was also, arguably, the closest thing to a truly self-regulating, self-sufficient, self-determining modern city that has ever been built.

The City in its final, massive high-rise form went back barely 20 years. In origin, however, the magistrate’s fort and the neighbouring Kowloon City were much the oldest parts of Hong Kong, and one of the few areas in Kowloon populated when the British first arrived in 1841 to claim Hong Kong Island and the southern-most tip of the Kowloon Peninsula for their own. It was a proper Chinese town, laid out with painstaking attention to eternal principles. The Chinese believed that a town should face south and overlook water, with hills and mountains protecting its rear, and in these terms the City was very happily placed, with the great Lion Rock just to the north of it and Kowloon Bay immediately to the south.

What the geomantic sages could not control were the infringements of the barbarians. When the British sought to expand their hold on Hong Kong in 1898, with a 99-year lease covering the whole of Kowloon Peninsula and all the nearby islands, most of Kowloon City was subsumed under the new jurisdiction. Under the terms of the lease, however, it was agreed that the small, walled magistrates’ fort to the north of the town, the Walled City, would remain Chinese territory. The situation was far from ideal and a year later, in 1899, the British government issued an Order-in-Council announcing that British jurisdiction was to be extended over the Walled City as well.

But the Order-in Council remained unilateral, and a diplomatic stalemate ensued which was only ended in 1987 in discussions following the Thatcher-Deng agreement on the colony’s future. Throughout the previous 90 years of British rule, the Walled City had remained an anomaly: within British domain, yet outside British control. The Chinese officials had left for good in 1899, but whenever the colonial authorities tried to impose their will, the remaining residents threatened to turn the attempt into a diplomatic incident. And so it remained until the Second World War, when the invading Japanese delivered the first body blow, tearing down the huge granite walls and using them to extend Kai Tak Airport in the shallows of nearby Kowloon Bay. The former harmony was destroyed: the creation of the airport had driven away the Yin spirit provided by the water and Kowloon City and its magistrate’s fort was largely abandoned.

The City may have effectively ceased to exist, but the area’s status as a diplomatic black hole was not forgotten, and in the chaos of the War’s aftermath it proved the perfect place of asylum for many of the hundred thousands of refugees pouring south to escape famine, civil war and political persecution as the Communists gained control in China. Surrounded now only by walls of political inhibition, the City became the place where they could get their breath back; where they could live as Chinese among other Chinese, untaxed, uncounted and untormented by governments of any kind.

And so, the Walled City became that rarest of things, a working model of an anarchist society. Inevitably, it bred all the vices that the enemies of anarchism denounce. Crime flourished and the Triads made the place their stronghold, operating brothels and opium ‘divans’ and gambling dens. Undoubtedly, these Triad few (and it always was a small proportion) kept the majority of residents in a state of fear and subjection, which is why for many years outsiders trying to penetrate were given the coldest of shoulders.

But for most, the main priority was survival and their needs were little different from anyone else’s: a life without interference with water, light, food and space. Of these water was the most indispensable and in the early years the only way to get it was to go down. And so that’s what they did, sinking some 70 wells in and around the City, to a depth of some 300 feet. Electric pumps shot the water up to tanks on the rooftops from where it descended via an ad hoc forest of narrow pipes and connections to the homes of subscribers. Only in the last 20 years were Government stand-pipes installed around the City to provide safe drinking water.

To run the pumps and to light up the City’s many alleys required electricity and initially this challenge was tackled in a similarly robust fashion: it was stolen from the mains, often by Hongkong Electric employees who lived within the City boundaries. Only in the late 1970s, after a serious fire (much the most terrifying hazard in the City), were the authorities allowed in with their meters.

Thus was the substructure of urban life roughly but workably banged into shape. And out of all the chaos and apparent lack of real organisation, a sort of society began to flourish. Soon, there were factories of every description, small shops and even schools and kindergartens, some of them run by organisations such as the Salvation Army. Medical and dental care were no problem, as many of the residents were doctors and dentists with Chinese qualifications and years of experience, but lacking the expensive licences required to practice in the rest of the Colony. They set up their clinics on the edges of the City and charged their patients a fraction of what they would pay elsewhere.

For the moments of relief from toil, there were many restaurants on the City’s fringes and embedded deep in its heart were a temple and a ‘yamen’, relics of the City’s distant past. And so life went on. Every afternoon the alleys were alive with the throb of hidden machinery and the clacking of mahjong tiles, while up on the roof, in cages not much smaller than some of the City’s homes, cooed hundreds of racing pigeons, joined there by children playing after school.

And here, in this richness and diversity, lies what was truly fascinating about the City. For all its physical shortcomings, and there were many, its residents had succeeded in creating a true community. For anyone who has wandered, enchanted and appalled, through the working-class back streets of Hong Kong or Macau, the photographs here will readily evoke the feel – and more importantly the smell – of the interior of the Walled City. But no images can do full justice to the experience of having been there. There were no thoroughfares and, except for a few bicycles, no vehicles – only hundreds of alleys and lanes, each different. From the innocuous, neutral exterior you plunged in. The space was often no more than four feet wide. Immediately it dipped and twisted, the safe world outside vanished, and the Walled City swallowed you up.

It was dark and incredibly dank. It was impossible to stand upright because the roofs of the alleys were lined with a confusion of plastic pipes carrying water, many of them dripping. Immediately you were in, the symphony of smells commenced: the damp, first of all and underlying all the others, then, as you progressed, of incense burning outside the homes, of charcoal and sweet-and-sour cooking, of raw and probably rotting fish, of burning plastic from a factory, of some sort of polish, of incense again and mildew.

The light was dingy at best, deep green; there was the endless spatter of water leaking on to stone. One particularly ghastly little ‘ginnel’ – spongily wet underfoot, a big rat hopping off – brought you to a gate of the Tin Hau temple. Its courtyard had been shielded from the rubbish routinely heaved out of upstairs windows by wire netting which, as a result, was liberally spotted with bits of ancient filth, through which a little daylight occasionally filtered down, just like the light that dapples through leaves in a forest.

All this intensity of random human effort and activity, vice and sloth and industry, exempted from all the control we take for granted, resulted in an environment as richly varied and as sensual as anything in a tropical rainforest. The only drawback was that it might be toxic. And then, there were the endless flights of stairs. Who would have been a postman in such a place? Yet there was an official postal service, and because the alleys and blocks often had no names or numbers, the postmen had devised their own system, roughly daubing complicated numbers at alley corners and building entrances to guide them.

You kept climbing and gradually it got a little better. The smells were diluted. Something like oxygen made its presence felt. The light brightened and finally you emerged at roof level, the only part of the Walled City where there was any space to spare. From there the awesome size of the place, which was essentially a single lump of building, became apparent.

The blocks were built at different times, of different heights and materials. Some were quite sophisticated: one of the largest, for example, was a copy of an early public housing block, ‘designed’ by housing authority architects in their spare time. Some had home-made annexes of brick or iron or plastic fastened on to the roofs, but all were jammed up flush against each other, so that an agile cat could circle the place at roof level without difficulty. The roof had various functions. One of the municipal services the Walled City never really got to grips with was rubbish collection. Most organic waste was taken away, but the inorganic – old television sets, broken furniture, worn-out clothes and the like – was lugged up to the roof and abandoned. In among these unaesthetic piles of junk, village life continued.

Washing was strung up between the thousand television aerials. Small children played something like hopscotch under the eyes of old ladies. Pigeons cooed sonorously. And every 10 minutes or so another jet descended on Kai Tak Airport – heading straight for the Walled City and, skimming so low, it was surprising that it did not make its final descent festooned in laundry.

What fascinates about the Walled City is that, for all its shortcomings, its builders and residents succeeded in creating what modern architects, with all their resources of money and expertise, have failed to: the city as ‘organic megstructure’, not set rigidly for a lifetime but continually responsive to the changing requirement of its users, fulfilling every need from water supply to religion, yet providing also the warmth and intimacy of a single huge household.

As the sun finally sets on this vast slum, there is perhaps cause enough to don rose-tinted spectacles and praise it.”

THANK YOU

The amount of goodwill that has surrounded the new edition from day one has been truly humbling and we cannot express our gratitude too much. It provided the impetus to set out on this journey and has continued to provide comfort and confidence when the task has seemed its most daunting. As anyone who has experience of producing a book of this size and scope will know, it is also an extremely expensive enterprise.

Greg and I have been working on the project for over 18 months, making numerous trips to Hong Kong in the process – from Vancouver on Greg’s part and from Wiltshire on mine – and numerous other contributors’ costs and expenses have had to be covered. This is not an exercise for the faint-hearted and we are particularly grateful to those friends and acquaintances who have offered their financial assistance along the way in the form of a confirmed orders. Henceforward to be known as Founding Supporters, we are pleased to list their names below with thanks to one and all.

Those who order single copies of the book either privately or through Kickstarter (see ORDER BOOK) before the end of March will also be listed in the book as ordinary supporters, but in exchange for a larger order (either for 5 books or for one book and one print) there are still places on the Founding Supporters’ list. Please contact ian@cityofdarkness.co.uk for details.

FOUNDING SUPPORTERS

Alex Choi Design • Nic Banks and Valeria Azario • Peter Basmajian • Richard and Lynne Bryant • Peter Clash • Jane Cowpe • Celia Davies • Richard Davies • Edge Architects • Nick and Debbie Elkins • Neil Farrin • Charlie Goddard and Charmaine Chan • Head Architecture • Johnny Kember and June Cheoh • Paul Kember • Andrew and Sue Lambot • Francis and Henrietta Lee • Robert and Christianne Long • David Marks and Julia Barfield • Sam and Gillian McBride • Nanette McClintock • William McElhinney • Nelson Chen Architects • Andrew and Elzabeth Reid • Martin Reise and Serena Chan • Charles and Diana Rodwell • Ann Seddon • John Small • Penny Sparke •

andyt • James T Areddy • Paul Barker • Robert Bielecki • Constance Brinkley • Eugene Britton • Oonah Buist • Terence Chan • Sonny Chiu Ka Ki • Darryl Condon • James Dowling • Jan Ivar Erno • Lily Fan • Mattijs Gevers and Marta Marotta • Jane • Samuel Kot Sing Chi • Nick Kraal • Peter Lau • Ben Lui • Emmy Lung • Florence Ma • michelle • One Space • Graham Osborne • Paramount Architecture • Robin Partington • Rinkoo Ramchandani • Christoforos Romanos • Stephen Sheng and Nina Lesser • Ting Fung Liu • Totoro • M Viamontes • Mathias Woo • Rufina Wu •

KICKSTARTER SUPPORTERS

Brendan Aaron • Anna Abbott • Bryan Acomb • Adrian • William Aegerter • Elsa Aevarsdottir • Glenda Ahn • Jan Ahrens • Carima Aichfakir • alanerapp • Tim Aldcroft • Anton Alenychev • Charles Alexander • John Alexander • Whitney Alexander • Philip Allison • Kevin Althans • Ebyan Alvarez-Buylla • Matthew Amster-Burton • Burkhard Anders • Svend Andersen • Kyle Anderson • Peter Andersson • John Andreas • Angela • anonymous • Ruth Ansari • Wesley Appell • Anthony D Archer • Marc Ardisson • Joseph Areddy • David Arlt • Espen Arntzen • Arsenic Playground • Rizki Arsiananta • Göran Arvidson • Aaron Ash • Tobias Asplund • Cindy Au • Jason Au • Vincent Au • David Austin • Stephanie Austin • Hawyee Auyong • Reinaldo Ayala • Maria Azamkhuzhaeva • Zach B • BA ~ EN • Ivan Baan • Noah Bacon • Nic Bailey • Carson Baker • Danny Bal • Justin Balog • Jeff Bannow • Barclay • Jacob Barker • Stuart Barker • Janel Barlongo • Betsy Barnard • Julia Barron • Hadley Bassett • Leonie Alfonsa Batalla • Tim Bateson • Baumeister • Gary Baydo • bayleaf • Richard Bean • J Beaumont • Megan Bedding • Beggs • Andrew Beirne • El Belky • Bryan Bell • David Bellis • Ben • Marcel Benard • David Bennett • Ber • Michael Ber • David Bermbach • Christine Bian • Jeff Biddick • Tim Binnion • Thomas Birchall • James Bishop • Jennifer Bishop • Libby Black • Jose Blanco • Shane Bliss • Susan Blumberg-Kason • Antoine Boegli • Carmel Boerner • Kevin Boetticher • David Bogart • Megan Boing • Muffy Bolding • Christopher Bolton • Maverick Bon • Jacopo Bonifaci • Pamela Bonino • Borangame • Vincent Boreux • Claire Bout • Richard Boyen • bradng • Alexander Brandt • Coral Brandt • Adam Brauer • Markus Breuer • Brian • Johan Brink • D Brisbin • Shay Brog • Mark Brown • Joshua Broyer • Roger Bruelisauer • Darren Brumfield • Bryan • Sean Bryson • Page Buckner • Nicholas Bulat • Ariya Bunyapamai • Marvin Buschendorf • Zachary Bush • James Bussey • John Butrovich • Gavin Buxton • bytor • Jeff C • Jonathan Cabildo • Philip Cahiwat • Jimmy Cailotto • Calmstock • James Cambourne • Joshua Cameron • Colin Campbell • Douglas Campbell • George Campbell • Scott Campbell • Douglas Candano • Bryan Cantwell • Chris Caramia • Salvatore Carbone • Paul Cardy • Pete Carlsson • Rick Carlton • Chris Carney • Robert Carnochan • Natasha Carolan • Simon Cartledge • Manuel Casal • Matthew Casey • Bruno Castro • Sity Cat • Josh Catone • Julian Cautherley • Frank Cava • Ellen Ch • Haresh Chainani • Raymond Challand • Lisa Chamberlain • Laurie Chambers • Chan Shu Wing • Ariel Chan • Chris Chan • Ernest Chan • Jason Chan • Leslie Chan • Michael Chan • Patrick Chan • Peter Chan Shu Kei • Philip Chan • Rita Chan • Selina Chan • Thomas Chan • Tom Chan • Yoanne Chan • Dennis Chang • Michael Chang • Jason D Chapman • Marianne Chapman • Tony Chappell • Charley • Ben Chatfield • Aries Chau • Fred Chavez • Ken Cheang • David Chee • Aric Chen • Louise Chen • Ross Chen • Xin Chen • Carl Cheng • Ernest Cheng • Galileo Cheng • Jennifer Cheng • Tiffany Cheng • Tony Cheng • Cheng Tsz Man • Ken Cheong • Zac Chester • Eddy Cheung • Eric Cheung • Ralph Cheung • Chihoi • Michael Chin • Chinese Album Guy • Chaiyaporn Chinotaikul • Stephen Chiu • Vivian Chiu • Edmund Choi • Tim Choi • Fai Chong • Chong Man Wai • Tiffany Choo • CHOR • Evan Chou • Tammy Chou • chr • Chris • Mark Chu • Wilson Chu • Conrad Chuang • chuck • Keith Chui • Eric Chun • Chun Kwong To • Anastasia Chung • Johnny Chung • Linda Chung • Peter Ciccolo • Rastko Ciric • James Clark • Paul Clarkson • Jacob Cohen • Colin • Christian Collovà • Robbie Colvin • Connie • John Connor • Darren Conway • Graham Cook • James Cook • Judy Cook • Liam Cooke • Eric Cooper • James Coote • Pierre-Henry Coppere • Laurens Corjin • Brian Cox • Julie Craddock • Brandon Creagan • Paul Croft • Scott James Crouch • Samantha Angeli Cruz • Ethan Currens • Mark Andrew Curry • Crystalfontz America Inc • Wolfgang D • Lauri Dahl • Haneen Dalla-Ali • Daniel • Mark Danzig • Dave • David • Celia Davies • Chris Davies • Pete Davies • Ted Davis • Bart-Jan de Brouwer • Alex de Campi • Gaelan D’Costa • dddilly • debagel • Ed Debevic • Decker • Andrew Delano • James Whitlow Delano • Roy Delgado • Fred Demarquette • E Scott Denison • Christopher J Dennis • Derek • Gabriele de Seta • Bradley DeVos • Nicole Dey • Brian Di Maggio • Simon Diffey • Thibaut Digard • DigiPhant • Daniel Dillard • John Dimatos • Rebecce Di Pasquale • Lisa Disterheft • Charles Dixon-Spain • E Dizon • Frank Djeng • Dominic • Caron D’Orazio • Maxwell Dorer • Molly Doria • Manuel Dornbusch • Daniel Douros • Doug Doyle • John Downing • Dan Drabik • Johannes Drechsler • Henrik Drufva • Taylor Drossel • Caleb D’Silva • Duarte • Deven Ducommun • Ian Dunbar • Duncan • Alasdair Duncan • Dashiell Dunn • Daniel Durkes • Brad Dutton • Mike ‘Dynamoth’ • Heinz Jörg Eberbach • Edmund • Vanya Edwards • Effects Database • Familj Effting • Neil Egbert • Mindy Ehret • Olaf Eichler • ejorpin • Martin Eliasson • Eline • Matt Elkan • Deborah Elkins • James Elwood • em • emily • empika • Logan Engels • Lawrence English • Michael Epstein • Eric • Lorna Lee Ann Erickson • Tony Ernst • Eseell • Reggie Estrella • Daniel Faria • Robert Farrell • Faulkenberg • Thibaud Fayolle • Sarah Feinman • Andrew Ferguson • Frances Ferguson • Ian Ferguson • Scott Ferreira • Andrea Fiechter • Andrew Field • Steve Figg • Ethan Fineout • Joseph Firrantello • Charles Fitzpatrick • Steve Flores • Diego Flumian • Thomas Flynn • Daniel Fogg • Alphonsus Fok • Ivica Folnovic • Sandra Forsyth • Forte • Deborah Foster • Fox and Badger Studios • Chris Fox • Joana França • Frank • Daniel Franklin • Fraser • Peter D Fraser • Evon Freeman • Alex French • Steven French • French & Michigan • Joel Frenk • Jay Friedkin • Sébastien Frooninckx • Fuat • Irwin Fule-Ver • Mari Fujita • Yoshihiro Fujita • Paul Fuller • Dominic Fung • Julian Furman • Todd Galloway • A Gammell • Carlos G Gananian • Tony Gatner • John L Gehron • Peter Gelfand • Matt K Gelgota • Robin Gelhard • Xavier Genot • George • Zsolt Geresdi • Alexander Getty • Cristina Giannina • Adrian Giddings • Gil • André Gil • Cheryl Gilbert • David Gilbert • Chris Gilson • Eva Smith Glynn • Brant Goble • Eli Goldfarb • LE Goldsmith • Ricardo Gomes • Irving Omar Gomez • Rob Gonzalez • Dylan Gould • Teresa Gowan • GPSPython • Grammaw • Denis Grangé • Bernard Gravel • Dan Gravitch • Glenn Austin Green • Michael Green • Green Teadog • Greg • Patrick Griffin • Rob Grimsey • Michael Gröning • Kristoffer Grönlund • Charlie Groves • Luise Guest • Phil Guest • Eric Gulliver • Marianne Gunderson • Hjalti Guölaugsson • Robert Gurney • Arthur Guttilla • Vicky H • Kris Haamer • Aegir Hallmunder • Johan Halse • Stefan Hammer • Mark Handel • Björn Hansen • Steve Hanvy • Mateo Hao • Omar Haque • Maxwell Harden • Paul Harding • harrison • Timo Hartwig • Hauke • Daniël Haveman • Manfred Havenith • Jeffrey Hawkins • Rob Hearne • David Heaver • Erik Hedin • Michael Heeney • Kristian Heinrichs • Michael Held • John Hellinkakis • Jaimee Hemphill • Douglass Henry • Kai Herchenhan • Gerhard Heuzonter • John Hewitt • Jesse Hicks • Isabella Hiew • Russell Higgins • Eddie Hilditch • Ian Hinden • Nick Hines • Enver Hirsch • Michael Hitchcock • H J • Holly Ho • Mabel Ho • Michael Ho • Suenn Ho • Zhiwei Wayne Ho • Dan Hobbes • Max Hödel • Adam Hodge • Ross Holder • Chuck Holland • Richard Hollis • Lisa Holman-Fyffe • Joseph Holmes • Matthew Horn • Jurie Horneman • Deanna Horton • Robert Horton • Håvard Riksheim Houen • Xavier How-Choong • Ian Howard • Ultann Lin Hsieh • Iris Hsu • Johann Richard Hsu • Frank Yifan Huang • Sean Patrick Huberty • Huck • Angelina Hue • Benjamin Hughes • Noel Hughes • Debbie Hui • Tai Hui • Paul Humphreys • Luke Hutchinson • Philip Huynh • Christopher Hylarides • Adi Ignatius • Mark Iliffe • Illyan • Martin Ingebrigtsen • Stéphanie Ionnikoff and Fabrice Rossi • Chris Irwin • Betsy Isaacson • Simon Isenberg • Stuart Isett • Humza Ismail • Kyle Isom • Erik Jacobsen • James13 • Mathies Janßen • Jasongip • Jay • David Jellings • Jess • Jessamyn • jino ok • Eli Jo • Joe • Patrik Purre Johansson • Anthony JN Johnson • jon • Chris Jones • D’Arcy Jones • juleeliz • Jung Joon Lee • Diana Jou • jwiechers • Tanya Kan • Fujio Kashimura • Courtney Kaupp • Benji Kay • Stephen B Keith • Chris Bla Keks • Kristopher Kelly • Paul Kember • Gregory Kennerly • Scottinlondon Kent • Kevin • Ameet Khara • khoshmar • Bartosz Kiera • Lawrence E Kilgour • Albert Kim • Dennis Kim • Kim Hoa Nguyen • Kin Chung Yu • Travis Kindler • king7879 • Brian King • Jared King • Luke Kingma • Kirk • Jonathan Kirk • Robert Kirkpatrick • Robert Kirkup • kitc • Dennis Klein • Matthew Klipper • Nils Klockmann • Kevin Kluck • Adam P Knave • Adin Knight • Donnovan Knight • Knight of Words • Sarah Knowles • Gray Kochhar-Lindgren • Greg Kodama • Beverly Kolb • Priscilla Kong Wai Yee • Gerrit Korff • Gergely Kováks • Jeffrey Krause • Sonja Krause-Harder • David Kregenow • Greg Kristo • Delta Kronecko • KT421 • Timothy Kubista • Stephan Kühne • Ben Kuller • Kwok Chern Yue • Ada Kwong Cheuk Lam • Philip Kwong • David Berdonces Labairu • Charles Lai • Alex Lam • Lam Fa • Lam Ho Ming • Jonathan Lam • Linda Lam • Sidney Lam • Tong Lam • Callan Lamb • Tommi Lampila • Kyle Lamson • Ken Lamug • Kristin Lane • Calvin Lang • Marvin Langenberg • William LaPlant • Claude Lardon • Jayme Last • James Latona • Andrew Lau • Declan Lau • Martyn Lau • Scott Lau • Tomy Lau Wing Yip • Lau Wai Ming • Grady Laughlin • Jack Lawrence-Brown • Lee EP • A Lee • Aaron Lee • Alvin Lee • Calista Lee • Carrie Lee • Charles Lee • Karen Lee • Lee Kin Chun • Maggie Lee • Matt Lee • Michael + Raymond Lee • Mike Lee • Steven Lee • Wesley Lee • Willis Lee • Oliver Leech • Takuto Lehr • Aki Leinonen • Wibbly le Mönde • Dan Lenander • Kenneth Leong • Mervyn Leong • Monta Lertpachin • Leslie • Joel Letkemann • Andy Leung • CH Leung • Christopher Leung • Dominic Leung • Eliza Leung • Jeff Leung • John Levin • Michael Lewarne • Amanda Li • Li Chak Fai • Jason Li • Keyang Li • Li Lo Ban • Ricky Li • Stan Li Cheuk Lam • Stella Li • Li Wing Yeung • Li Zong Xian • Joanne Liang • John CP Liauw • Lillian • DJ Lim • James Lim • Lindsey • Chad Lindsey • Tony Ling • linkaaa • Jim Lippard • Melas Lithos • Chee Liu • Jason Liu • Paul Liu • Becky Llewellyn • James Nathan Lloyd • Ernie Lo • George Lo • Ivan Lo • M Lo • Rich Lo • Joseph Locher • Nicholas Loepp • Jure Logar • Loh Sheng De • Loi Wai Kit • Lok Tin Ho • Sonya Loke • David Sierra Lopez • Jenny Lovell • Katherine Lu • Gerd Ludwig • Lugana707 • Kenneth Lui • Lui Kwan Wo • Andrew Lum • Philip Lun • Emmy Lung • John Lunney • Abby Lusk • Mikhaila Lynn • Kayleigh Ma • James Mabe • Fergus MacDermot • Dan Macheski • Mike Machian • Ryder Mackay • Maddie • Patrick Magee • The Magenta Foundation • Meg Maggio • Mateen Mahboubi • Fraser Maitland • Casper Mak • Aemon Malone • Malcolm Mallory • Nicole Manders • Kenneth Manning • Elizabeth March • Marcus • Mike Mariano • Mark • Angela Marsh • David Mårtensson • Andrew Martin • Alex Martinelli • Olivier Martinet • Julian Martyn • Anastasia C MasOen • Adrienne Massanari • Eduardo Matamala • Matthew • Roy Maurer • Max • Christophe Mayol • Jakob Mayr • James McAlister • Connor McBrian • Michel McBride-Charpentier • Taylor McCarra • Emmett McCarthy • Will McCollum • Judith McConnell • Christopher E McDade • Alex McDaniel • John McDermott • Robert M McDunn • David McEvoy • Matthew McGale • Matthew McGrath • Feldore McHugh • David McKellar • Elven McKnight • Lori McMillan • Derek Mead • Virginia E Mead • Alexander Mel • Stuart Melton • Kenn Melvin • Merlot the Sheltie • Hugo Mesquita • metatim • Simon Methi • Osman M-G • Patrick J Michel • Jonathan Miller • Menandro Miranda • Sarah Miranda • Alicia Mitchell • Brian Mitchell • Stefan Mlakar • Nancy Mock • Veronika Mogyorody • Palani Mohan • Malcolm Moore • Taylor Moore • Arthur Morriën • Taylor Morris • Julien Mudry • Denny Mui • Jeremy Muir • Jeppe Mulich • John Stewart Muller • Richard Owen Murdoch • Jeff Myers • Hugh N • Jacob Nadal • Yuta Nakahara • NakedTrust • Nando • Sheela Narayanan • Natalie • Dominic Naughton • Miguel Navio • Mike Naylor • Man Naz • Lawrence Neeley • Alex Nercessian • Jonathan Nesbitt • Leslie Newman • Matt Newsome • Philip Newsome • Chris Newson • Steven Newton • Alice Ng • Ng Ho Yin • Jessica M Ng • Roydon Ng • Scott Ng • Carol Nicolle-Tsiakos • Heiko Niebur • Nick • Victor Nicolle • Brandon Nightingale • Masaki Nishino • William Niu • NoBone • Raymond Nordin III • Chris Noury • Kirk Norton • Rob Notigan • nurin • Benjamin Nuttin • Greg Nyman • Andrew Odri • Oeli • Beatrix Oetting • Gui Ohm • Philip Oldfield • oliverz3d • Sean O’Mara • Adam O’Neill • Andrew Oppeneer • Tim O’Rourke • Niklas Ortheil • Lars Os • John Ossoway • Owen • paiciee • David Pandt • Amos Pang • Cecily Pang • Jason Pang • Jose Daniel Gual Pantoja • Nicholas W Park • Alexander Parker • Jaime Parsons • Marc Parsons • Robin Partington • Nicholai Peter Patchen • Nirav Patel • Patrick • Paul • Leland Payton • Derek Pearcy • Casey Pedersen • Pedro • Marlene Perks • David Perry • Jon Pestana • Levi Peterffy • Alden Peters • Nathan Peterson • Allen Petlock • Yen Pham • pharmac • Alan Phillips • Dave Phillips • Lane Phillips • Crystal Pickard • John Pike • Josée Plamondon • Anastasia Pleasant • Dennis Marcel Poepperi • Jonathan Polansky • poltergeister • Chris Pomery • Bryan Powell • Leighton Pritchard • Frank Proctor • Adam Proehl • ProgramCat • Jason Puglionesi • David Pulleine • Patiya Pullket • pwandz • Chris Quackenbush • Kally Quah • Joshua Radu • Peter Radünzel • Caelum Rale • Louie Ramos • Pedro de Spinola Ruella Ramos • Eric Ransdell • RaTTuS • Zachary Rawlins • Daniel Raynes • econfig2501 • Robert Anton Reese • Ortwin Regel • Kraig Reiber • Charles Reid • Tjerk Reijenga • Andy Rennie • ricarter • Robert Richardson • Turk Ritz • Nicholas Vaughan Roberts • Euan Robertson • Abby Robinson • John Robinson • Philippe Robinson • Eliot Rockett • Álvaro Manuel Rodríguez • Jeff Rodriguez • J Lee Rofkind • Pieter Röhling • rolf_nei • Luke Rooney • Rory • Garett Rose • Adrian Roselli • Adrian Rosenthal • Fabian Rosenthal • Bobak Roshan • Edmon Rotea • Mark Roudebush • Rowat • Christopher Rowe • George Roy • John Roy • Esteban Rujillo • Jonathan Salerno • Kenneth Salmon • Leslie Salmon-Zhu • Javier I Sampedro • felix sanchez + wong chan wei • Wayne Santos • Sarmax • Riccardo Sartori • Holly Saunders • Greg Sauter • Micha Savelsbergh • James Saywell • David Schalliol • Jorren Schauwaert • Gerhardt Schellert • Cristoph Schmalenbach • Jurgen G Schmidt • Maren Schmohl • Dylan Schneider • Susanne Schulz • David Schwab • Sibylle Schwarz • Graham Scott • Kate Scott • Nicholas Scott • Paul Scrivens • Roman Segal • Reece Selwood • Vital Sementsov • Veen Senn • Arnold Serame • Mike Serritella • Lyn Setchell • Eric Sharp • Margaret Sheer • Sohaib Sheikh • Noah Shelton • Qilai Shen • Eric Shepard • Shi Jian Chiou • Patrick Shine • Ruth Shinnick • Stephen Shiu • Jack Siegel • Siew Wai Poon • Sacha Silva • Alison Sime • Simon • SimpleWorks • Mark Simpson • Jacob Sims • Benjamin Sin • Lucia Siu • Olivia Siu • Ronald Siu • Siukai Siu • Ventus Siu Tsz Fung • Haema Sivanesan • Mario Sixtus • S-JY • Jacqueline Skelton • Eduardo Skinner • SkinnyV • Aviya Sl • Ruth Slavid • Geoffrey Sledge • slothglut • John Small • Laurel Smith • Rasheeda Smith • Alex So • William So • Tim Soane • Antonio Socrates • Soren Sodergren • Felix Varjord Söderström • Matthew Sokol • Carlton Solle • Marc A Solondz • Marco Sparmberg • Mark Sparrowhawk • Jessica Spengler • spilgrim91 • squidamus • Stephen Stanridge • Hendrik-jan Stalknecht • Catherine St-Cyr • Jane Steer • Mike Stenhouse • Stevek504 • Joel Stevenett • Alex Steyermark • Alison Stieven-Taylor • Jordan Stone • Craig Stowers • Johanna Strandman • Gheneral Stuff • Spring Suave • Brian Suda • Jack Suen • Michael Suen • Alexander Summers • Angela Sung • Surse • Daniel Svegert • SVR The Boy • Will Swales • Jason Swamy • Matt Sweeney • M Sydow • SympathyPlan • Tony Szedlak • Neil Ta • Michael Tabacinic • Alex Tabarrok • Michael Tak Ko Luk • Cherrie Tam • Frit Sarita Tam • Juston Tam Chi Shing • Summie Tam • Terence Tam • Tamas • Aen Tan • Jon Tan • Quinnie Tan • Didi Tanadjaja • Alex Tang • Howard Tang • Jansen Tang • Tang Kian Wee • Tang Kwok Chuen • Marvin Tang • Patrick Tang • Adam Taylor • D Taylor • Ted • Televangelist • Stephanie Tennant • Julio Terra • Sam Thacker • David Thai • Michel Thein • Janice Thomas • Jennifer Thomas • Cameron Colby Thomson • Tiffany • timto • Philip Tinari • Matthew Titsworth • To Cheuk Yin • Guilherme Toews • Toffile • Tom • Robert Tomaino • Grant Tomasino • Louis Tong • Simon Tooke • Juan Miguel Torres • Karin Totterman • Alex Tsai • Keith Tsang • David Tschida • Martin Tschiersky • Edward Tse • Edwin Tsui • Jonathan Tsui • Michael Tsui • David Tudino • James Turnbull • Mark Turner • Keith Tyler • Paul Unett • Ugol Woodworks LLC • Corey Unwin • Simon Unwin • Jan Urschel • Martin van den Nouweland • Nick van der Kolk • Nathan van der Waa • Sander van der Wel • Leslie van Duzer • Blake Vaughn • Kash Vazirani • Vesper • Jeffrey Vest • Kris Vervaeke • Frederik Vezina • Mark Vicente • Mark Vidovich • Shelly Vingis • Petr Vochozka • w5748 (Jesse) • Ann Wagner • Wai Kin Ng • Patrick Wai • Mark Wainger • Adam Wakeling • Michael Walker • Aidan Wallace • Anthony Wallace • Antony Paul Wallwork • Shane Walter • David Walters • Horus Wan • Ron Wan • Wan Yan Wong • John Wang • Judy Wang • Matthew Wang • Phil Wang • Gary Ward • Wang Tien • Andrew Wareham • Luke Warm • Jeroen Wassing • The We Collective • Gerhard ”ScHIAuChi” Weihrauch • Ross Wendell • Weng Cheong Ann • Andreas Wessler • Simon Westcott • Joel Westworth • Cinnamon Whaley • Zac White • Kendall Whitehouse • Andrew Whitehurst • Emmet Wickham • Lyndsay Wiens • Florian Wild • Helga Wilker • Sean Wilkie • Will • Doug Williams • John E Williams • Kevin Willock • Andrew Wilson • Matt Wilson • Noah Wilson • Patrick Wilson • Stuart Wiltshire • Chris Winczewski • Guillaume Windels • Wing Ho • Mike Winters • Elaine Wisbey • Scott Wittbecker • Ryan T Wolfe • Martin Wolfertz • Daniel Wolff • Andreas Wolmer • Carl Wong • Chun Wong • Dagan Wong • Hans Wong • Isaac Wong • James Wong • Jeffrey Wong Tsz Nam • Jimmy Wong • Joe Wong • Wong Kar Wing • Keith Wong • Martin Wong • Martin Wong • ND Wong • Norman Wong • Wong Oi Wah • Ray Wong • Sonny Wong • Suzanna Wong • Wong Tai Sin • Tesby Wong • Veronica Wong • Cyris Woo • Elias Herse Woo • James Woo • Julie Wood • Patrick Woods • Ernie Woody • Chris Wright • Jo Wright • Danny Wu • Dixon Wu • Urs Wuest • Wun Sze Li • Rick Wyckoff • Leo Wyndham • Rhoda Wynn • XoXo • XOoET64oOX • Nathan Yam • Denny Yan • Yan Kae Kor • Wailun Yan • Adrienne Yang • Bill Yang • Mark Yang • Soichi Yano • David Yao • Chris Ybarra • Brian Yeung • Jason Yeung • Jason Yeung • Pete Yeung • Ryan Yeung • Gordon Yip • Helen Yip • Stephen Yip • Sophie Yiu • Yoshio • Gilly Youner • Cara Young • John Yu • Karen Yu • Margaret Yu • Stephanie Yu • Ivan Yuen • Waldemar Yuen • Herman Yung • Steven Zakulec • Tieg Zaharia • Reuben Zaramian • Nicolas Zeggers • Tammy Zemel • Amy Zhang • Xi Zhang • Ellen Ziegler • David Zielinski • Marc Zoe • Andrew Zuber • Ethan Zuckerman • 300rwhp

BUILDING M+

With tourism an ever more important part of Hong Kong’s economy, the Hong Kong government has invested in a number of schemes in recent years, aimed at positioning the city as an exciting ‘destination’. And among the most ambitious of these is the West Kowloon Cultural District, a major new centre for the performing and visual arts soon to break ground on reclaimed land alongside the southern tip of the Kowloon Peninsula, overlooking Victoria Harbour.

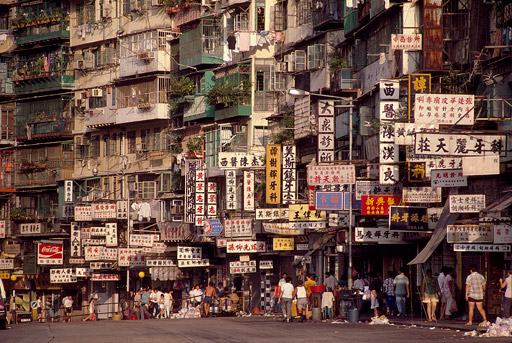

Several new venues, many by major international architects, are planned for the area, perhaps the most audacious of which is M+, a new multidisciplinary museum dedicated to the visual culture of Hong Kong, China and the surrounding region, focusing on 20th and 21st century art, design, architecture and the moving image. Designed by the renowned Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron (in association with TFP Farrells and Ove Arup & Partners HK) and due for completion in late 2017, the future M+ building was unveiled to the public at a recent exhibition in Hong Kong, the fifth in a series of Mobile M+ events called ‘Building M+ : The Museum and Architecture Collection’.

Here, alongside a detailed exploration of Herzog & de Meuron’s new design and an overview of the other short-listed schemes, was a major display presenting for the first time the museum’s growing and unprecedented architecture collection. In just 10 short months the Architecture collection’s curator Aric Chen and his team have so far amassed a stunning collection of around 1000 drawings, models, videos and photographs, an astonishing achievement for a totally new type of museum with no precedent in the region and, indeed, very few worldwide.

And among the 100 or so items Aric and his team decided to display, we are pleased to say was a brand new archival-quality photograph of the Kowloon Walled City: the aerial view beloved by so many websites but now printed properly to the highest standards and on authorised public display for the first time. Like the rest of the items on display, the print will go on to become part of the M+’s permanent collection.