WATER FIT TO DRINK

Like much else in the Walled City, the provision of a reliable water supply was the source of considerable inventiveness and entrepreneurial skill, not all of it healthy. The Government’s long-standing refusal to connect individual buildings, apartments and factories into the external mains system, and thereby legalise water supplies, meant the City’s residents and businesses had to resort to paying private suppliers, to pump water from wells sunk beneath the City, or local Triad groups for water tapped illegally from nearby mains supplies.

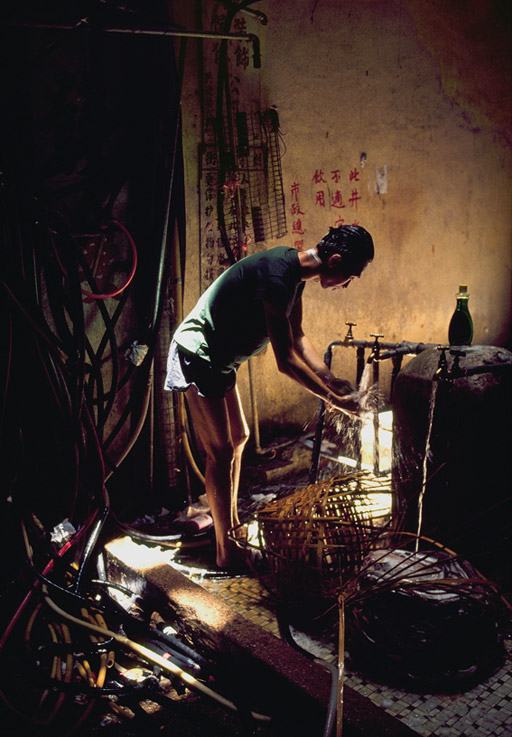

The only concession the authorities made over the years was to install a few public freshwater stand-pipes, though these were barely enough. By 1987, just eight stand-pipes were in place to supply up to 35,000 residents and hundreds of factories. Only one of these was located within the City, while the remainder were positioned, inconveniently, outside its perimeter. Running mains water was supplied to various recognised charities inside the Walled City, but this was very much the exception not the rule.

The first stand-pipe was installed in 1963 giving the city, in the words of a Government statement at the time “access to a free, unrestricted water supply”. Residents had a somewhat different perception. Representatives of the newly formed Kai Fong Association, calling on the Secretariat for Chinese Affairs in 1964, complained of the acute shortage of water at a time when “the Chinese Government is working selflessly on the East River scheme to provide ample water for Hong Kong residents”. Their complaints were well grounded, if dressed in rhetoric. Four emergency hydrants had been removed following the end of the drought that year, leaving just five stand-pipes. Residents were paying $12 – 15 a month for labourers to carry six kerosene cans of water each day from the stand-pipes to their flats in the jumble of then mostly two- three- and four-storey buildings.

The business of carrying water for entire households became increasingly difficult the more the City grew skywards, during the boom days of the late 1960s and early ‘70s. Rapidly expanding demand, notably from new and thirsty factories, and the impracticality of trudging six or more storeys to individual apartments drove entrepreneurs underground to tap new sources. The new well diggers were mainly property owners who were able to drill on their own land; some were reputedly former water-carriers themselves.

There had been wells in the City in its earlier days. One former resident recalls water being collected from a couple of wells at the northern and eastern gates immediately after the War. By the time the clearance was announced in 1987, Government surveyors assessing compensation claims identified 67 working wells owned by some 40 suppliers. Over the years, up to 300 ‘scientific wells’ – as they are described by City-dwellers – are said to have been sunk beneath the area, though many had long run dry from overuse. The more recent drillings had to reach as far as 100 metres below the surface, as shallower sources had been depleted. Private drilling firms were contracted to carry out the work.

Physically transferring the water to residences was usually a crude, makeshift process. Water was first pumped up to rudimentary storage tanks on the City roofscape. From there, a twisted congestion of pipes ran downward again, branching into blocks and flats. Installation of a well-water link could cost as much as several thousand dollars, depending on the height above and the distance from the well. By the late 1980s, monthly charges were anywhere between $50 and $70 per household.

Despite reports of numerous people being unable to afford the steep connection fees, the majority of City residents appear to have been linked up to receive well-water. A simple connection in itself, however, did not guarantee the end to one’s water problems.

Pressure and pumping difficulties meant that many pumps would only be turned on at set times – usually noon and midnight – to replenish the tanks. This would only give a few hours’ supply, and it meant that residents still had to store water in baths and buckets. About 20 people were employed to control the supply at various locations according to the well-owner’s schedule.

Perhaps the biggest drawback with the well-water, though, was that much of it was undrinkable. Pungent and murky, it was impregnated with the usual seepage or urban and industrial pollutants. The best use it could be put to was washing and floor-cleaning; much of it was not even fit to boil. Drinking and cooking water still had to be carried from the stand-pipes, and a small workforce was engaged in this activity till the end.

Health problems were also a major concern. Before the Government got together with the Kai Fong to install a mains sewage line in the 1970s, raw human waste exited the City via open drains driven down the side of the tiny streets. Much of this sewage seeped away, forgotten, into the ground, leaving the underlying geology of the area like a giant septic tank. Underground sources, especially from the shallower wells, could not help but be contaminated.

The installation of a sewage mains was one of a number of essential services the Government felt compelled to provide. Like basic policing and lighting, and the provision of social services and rubbish removal, it was one of the several exceptions that broke the rule of non-intervention. It was, in a sense, the other necessary side of the coin to water supply, which the Government had allowed to be managed privately without regulation – extra-legally but not illegally. But sewage and waste removal was a matter of public hygiene, and had implications for the health of people beyond the City.

In later years, there were numerous calls to improve the situation by providing mains water more widely, but by then the authorities were able to cite the technical difficulties presented by the City. First among these, the Government argued, was the high concentration of buildings, none of which had adequate provision for water or waste. Second, there were the narrow streets and the sheer disruption that laying mains pipes would cause to City life. These were certainly valid considerations, but more important, perhaps, was a continuing reluctance to further encourage permanent settlement in the City, combined with the knowledge that more accessible pipework would only invite ever extending illegal connections.

Wells were not enough in themselves to supplement the eight paltry stand-pipes. Consequently there was some illegal tapping of mains water from outside the City, notably from the adjacent Sai Tau Tsuen and Mei Tung estates. This illegal business was monopolised, in the beginning, by the Triads. As these same organisations were also involved in much of the construction in the City, they were able to ensure that the newer buildings, at least, had some provision for water supply and waste – even if only of the most rudimentary kind – or could impress on the buyers the benefits of being connected.

Several competing water suppliers might also be competing for business in one building, particularly where the building was not owned by a single proprietor. Once a household was connected to a particular supplier, there were clear rules of business-client behaviour. Residents would generally pay on time for fear their water would be cut off or their pipes damaged. Fee collectors would tell customers that their dues were partly for the upkeep of the system and partly for bribes to officials. For some residents it could mean more than a simple business relationship.

The Triad leader who, in 1980, laid down the law on a price rise is one case in point. “Whoever dares to take the lead in opposing the hike”, he said, “we’ll chop him up in front of the crowd.”

In time, the Triads sold off most of their ‘business’ interest in the City, but the illegal tapping of mains water remained an important source of drinking water until the end. Those involved in the clearance are reluctant to admit how extensive this practice might have been, but it is unrealistic to assume that 33,000 people and 700 businesses could have been supplied by 67 ground wells alone. The decision was made that it was better to turn a blind eye. To close down the illegal supplies would have caused unnecessary hardship for the residents and brought increased resentment. It was easier to clear the City and solve the problem once and for all.