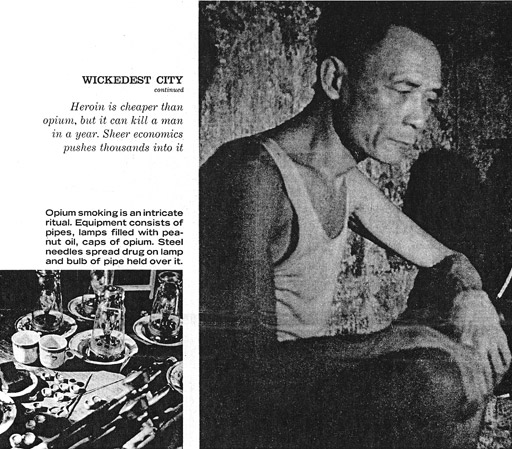

THE WICKEDEST CITY

Searching through the numerous files to be found in Hong Kong’s Public Records Office, either real or on microfilm, that refer to the Walled City can easily become addictive. Every folder seemed to turn up some fascinating detail or, as in this case, a long lost article that probably hasn’t seen the light of day in over 50 years.

Written by a young American journalist, Cathie Breslin, and published in the Toronto-based magazine The Daily Star in November 1963, the article recounted Breslin’s visit to the Walled City in search of an opium den. Raised in Massachusetts, the daughter of a pediatrician, Breslin had graduated from the University of Toronto in 1957 as a history and philosophy major before opting to try her hand as a journalist.

Horrified by, in her own words, the “sexual ghetto” of Canadian journalism at that time, where she was “flung onto the women’s pages”, Breslin decided to go freelance, working in Canada and the USA for a few years before leaving for Southeast Asia in 1961. She was to remain there for the next two years, travelling round the whole region including Vietnam, saying later that, “the war at that time was almost fun … Vietnam wasn’t really cranked up yet.” This was clearly no ordinary young American ingénue.

Entering the Walled City with Chinese photographer Eddie Chan, they met an opium addict they refer to in the article as Cheng who agreed to help them on their quest, taking them to his home while he made the necessary arrangements:

“Cheng’s smooth, boyish face belies 40 troubled years. A former Nationalist policeman turned narcotics hustler, he has worked ‘in this business’ since coming to Hong Kong 14 years ago. His job entails sizeable risk, but only pays 80 cents a day. Plus 16 cents for ‘lunch’.

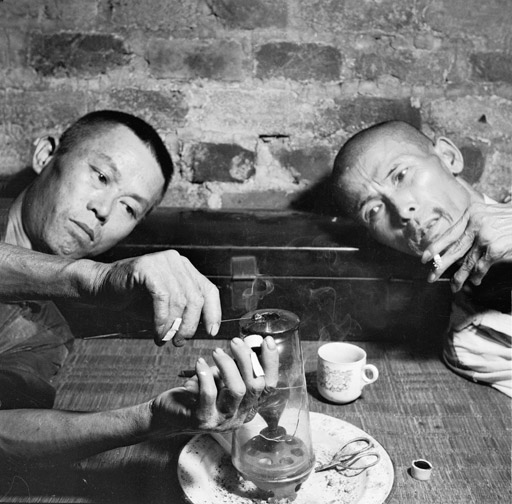

An hour later Cheng went off to fetch the opium. His plump, pretty wife arrived home with her two small sons. Cheng returned with a friend, Lai, their arms loaded with newspaper-wrapped bundles, and ordered his wife and children into the alley. He had bought a new $5 pipe for the occasion – so cheaply made that he had to bind it together with a strip of silk. He complained that they don’t make them now the way they did in ‘the old days’, when opium represented gracious living in China.

The pipe assembled and the peanut-oil lamp lit, Cheng grabbed two large cans to serve as pillows. He and Lai stretched out on the linoleum bed and began the intricate rite: they sizzled the ‘cooked’ opium on top of the lamp, smeared it on the rim of the pipe’s rubber bowl and scraped off the blistered ash. The babble from the alley seemed to fade as Lai took whistling pulls on the pipe.

Since coming to Hong Kong I had wanted to try this forbidden ritual. I tapped Eddie on the shoulder: ‘Can I try a puff?’ Startled, he translated. Cheng scrambled off the bed and gave me his place and pipe. ‘What do I do now?’ I asked Eddie. ‘Just smoke it like a cigarette.’ Although I smoke I don’t inhale. When my big moment came I drew in mightily; I seemed to be pulling smoke to the bottom of my lungs. I went dizzy from sheer effort.

If everybody got as little a kick as I did from an opium smoke, Hong Kong would have an enormous problem solved. Government surveys reveal that the majority of Hong Kong’s estimated quarter-million narcotics addicts are middle-aged, low-salaried workers looking for relief from the ‘stresses of their everyday lives’. Lai is typical. An ex-fruit peddler, he has smoked for 15 years. He stopped once when he realised it was killing him, but a stomach ailment drove him to start again. ‘When I smoke,’ he says, ‘I feel no more pain and I can smile again.’ Now unemployed, he hires himself out to tend the pipes of more affluent smokers and smokes up their leftovers.”