A LEGEND IS BORN

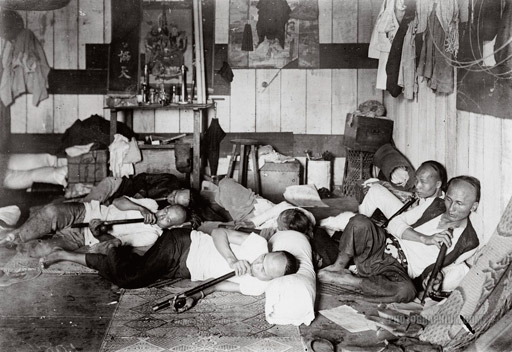

An opium den in Hong Kong in the 1950s.

The failed attempt to clear the Walled City of squatters in 1947 left the Hong Kong authorities in a quandary. Before the War the Hong Kong government had felt they could act with impunity, actually evicting several pig farmers from the City’s confines in the 1930s. The Kuomintang government had raised its objections, but the situation in China was so confused that the powers to be in Hong Kong felt these could be safely ignored.

By 1947 this was no longer the case. The severe deprivations Hong Kong had experienced during the War had taken their toll and the ease with which the Japanese had been able to occupy the city in 1941 had shaken the authorities’ confidence. The situation in China was also changing rapidly, with Mao Tse Tung and his communist forces on the rise, though what his intentions might be, in particular with regard to Hong Kong, remained a mystery.

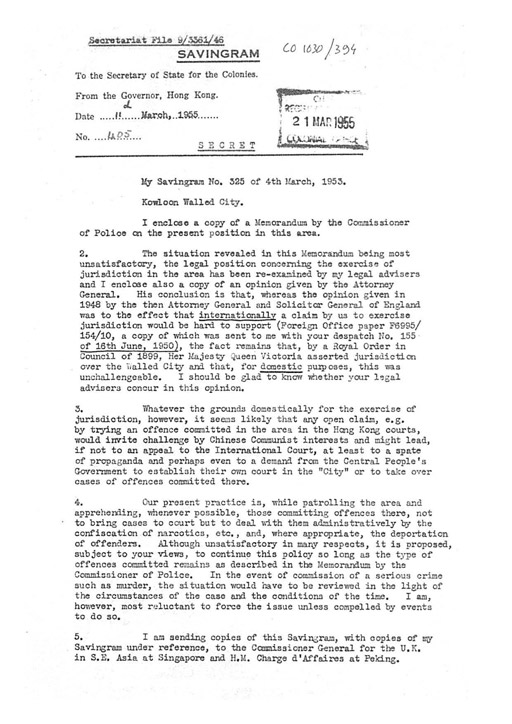

The flood of refugees into the territory through 1948 and 1949 was soon giving the Hong Kong government more to worry about than the Walled City, but until the situation in China had resolved itself they had already decided that caution was the better part of valour and that no further action would be taken in the Walled City that might cause the authorities in China to object. And when this came down to the issue of dual jurisdiction, this would include police activities there and, more importantly, prosecution of those who broke the law.

The Hong Kong authorities were keenly aware that if they attempted to prosecute anyone arrested for a crime within the City, this potentially opened the door for the Chinese government to step in and claim equal rights, possibly demanding that a Chinese court be set up inside the City. It is doubtful this was on the Chinese government’s mind at the time, but the decision was made that for the time being at least no-one arrested in the City would be charged with any form of criminal offence.

Covering letter to the 1955 report, detailing the concerns about taking Walled City residents to court.

The police would continue to patrol the area and arrests would be made, but apart from a night or two in the cells and the confiscation of illegal materials, most notably drugs and drug paraphernalia, no further action would be taken. Some minor cases were prosecuted through the civil courts and the most serious offenders, usually known Triad bosses, were repatriated to China, but otherwise the Walled City’s residents were largely left to their own devices. Unsurprisingly, this state of affairs did not go unnoticed and soon Triad gangs were flocking to the City, keen to set up any illegal operation they could think of.

Unlike their mafia and camorra counterparts in the West, the Triads have no real central structure and for the most part are made up of a loose alliance of individual street gangs that claim allegiance to one Triad or another. Power within the Walled City was split roughly between the 14K and Sun Yee On factions which, when they were not fighting each other, tended to be involved mainly in low-level criminal enterprises, notably protection rackets, control of the sex industries and ‘street-corner’ drug dealing.

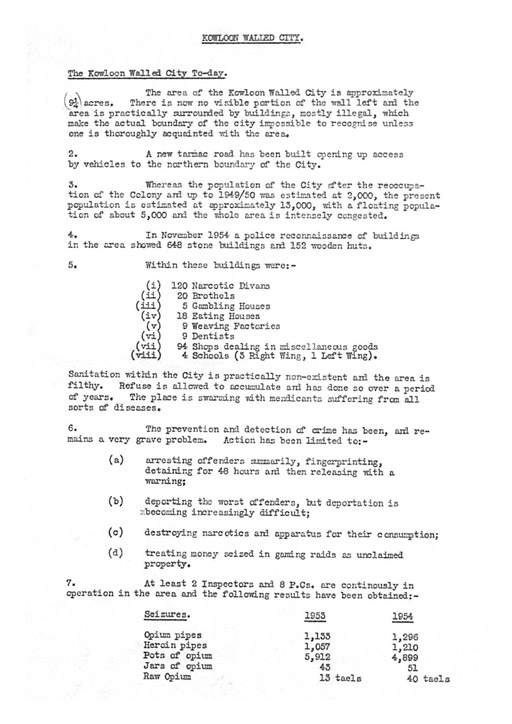

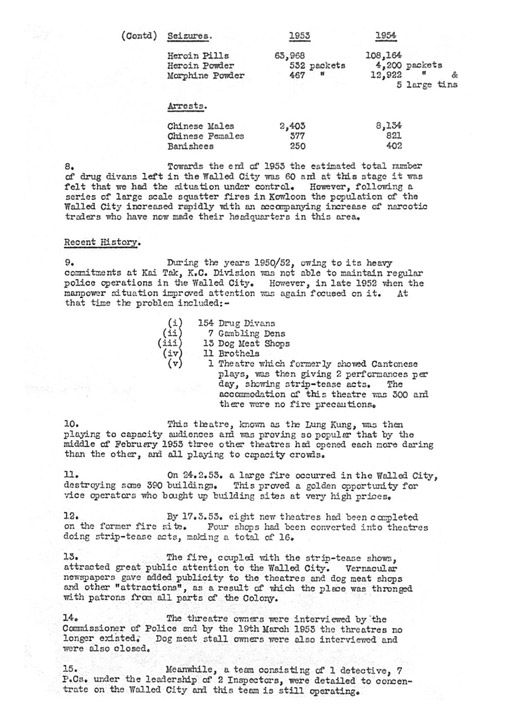

With the minimum of police interference, such activities boomed, with one police report, drawn up in 1955 in response to questions raised by the Foreign Office in London, noting the presence as early as 1952 of 154 drug divans, seven gambling dens, 13 dog meat shops, 11 brothels and one theatre giving two striptease performances per day. If nothing else, not only does the report confirm that the police were patrolling the City, but more importantly that they had a pretty detailed knowledge of what was happening there.

And indeed attempts were made to try and bring the situation under control, but the maze-like layout of the City, an alert band of lookouts and, no doubt, tip-offs from within the police force itself, meant large-scale raids almost always arrived too late after most of the participants had left, leaving only a smattering of comatose opium addicts and a few older prostitutes who were too slow on their feet. Drugs and the apparatus of opium smoking were confiscated and certain properties were closed, but the Triads considered this a small price to pay and operations could always continue in another location almost without a break.

The 1955 police report gives an unrivalled glimpse of what life was like in the Walled City at the time.

And so the situation continued. By the nature of the times, too, in some quarters the Walled City took on an almost glamorous quality, with the film stars of the time arriving in smart cars which were left parked on Tung Tau Tsuen Road while their occupants disappeared into the City to taste dog meat or other delights. The Triads also proved adept at adapting to prevailing trends. The same 1955 report notes a sudden surge in striptease parlours when the Walled City started becoming a recognised stop for Japanese sex tourists keen to see what Hong Kong had to offer.

But the times were changing and the heyday of Triad control in the Walled City was soon on the wane. And not so much because the police were managing to gain a degree of control, but rather because corruption within the police force was becoming so endemic that the Triad gangs no longer needed to hide away in Hong Kong’s darker corners, but rather could operate in the open in the parts of town where more money could be made. There would still be some crime in the Walled City – sometimes more, sometimes less – but the total freedom that the Triads had enjoyed there for that brief period would never be matched.

For a time, though, the Walled City really could have been described as a den on iniquity, and it was a vision that the City was never able to escape. The times changed but the myth lived on.

Contrary to popular belief, daily police patrols were a regular part of City life from the 1950s onward.