A BOY’S OWN ADVENTURE

A publisher of poetry and a prolific poet and author in his own right, the British born writer Martin Booth spent most of his school years in Hong Kong, arriving as a seven year old in June 1952 after his father had been posted there to take up an administrative role in the Royal Navy.

An only child of parents whose marriage was slowly disintegrating, the young Martin was left very much to his own devices, and within weeks he was spending much of his spare time out and about on the streets of Kowloon, making friends with the local shopkeepers and rickshaw drivers, and quickly learning more than enough Cantonese to get by.

Precocious and highly inquisitive, he was soon wandering over large areas of Tsim Sha Tsui and Yau Ma Tei from his parents’ lodgings in the Four Seasons’ Hotel, but towards the end of 1953 the family was reassigned to an apartment on Boundary Street, across on the eastern side of the Kowloon peninsula.

Warned by his mother, within a few days of arriving there, that on no account was he to go near the Kowloon Walled City, Martin of course made it his business to immediately go and check out what this mysterious place might be and, over the next few months, he made several visits, being introduced to different parts of the City by two characters who befriended him there, Ho and Lau.

Returning to the UK in 1964, Martin continued to travel in Europe and the USA as well as the Far East as his literary career took off and established itself, but as he himself noted: “It had never been my intention to write an autobiography. To do so smacked of arrogance: it was not as if I were a rock star, an explorer, a footballer or a member of the miscreant aristocracy. It is true that I have had an interesting and remarkably lucky life, but that is far from unique and I never thought to document it.”

But in 2002, at the insistence of his children following the diagnosis of an especially malignant form of brain tumour, he decided he would “tackle the task” of writing about his childhood. “Once I had set out upon the task, the past began to unfold – perhaps it is better to say unravel – before me. I did have some assistance in the form of a scrapbook and several photograph albums my mother had compiled, yet these did not so much prompt as confirm certain memories, flesh out anecdotes that have spun in mind for years, rekindle lost names and put faces to them.”

The book that resulted is the highly regarded and much loved ‘Gweilo : a memoir of a Hong Kong childhood’, which he was able to complete shortly before the tumour finally claimed his life in February 2004. The following extracts recount his memories of visiting some of the more unusual places in the Walled City.

“We walked on. Suddenly, Lau stopped and said, “You no like other gweilo boy.” For the first time, he touched my hair. “Now I show you good place.”

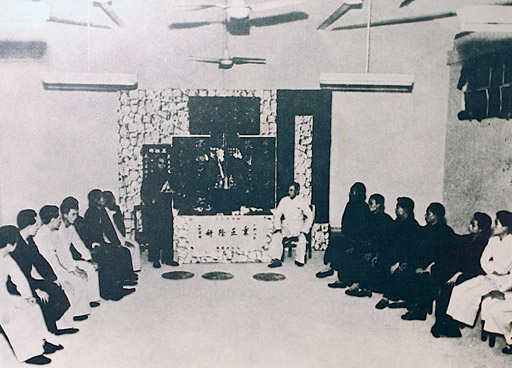

Our destination was the balustrade building I had visited on my first excursion into the Walled City. We entered it, passed through the downstairs room, still devoid of occupants although I could hear the noise of snoring emanating from upstairs, went behind the screen, out through a door into what might have been a flagstoned courtyard and down some steps to a semi-cellar about thirty feet square. At the bottom of the steps was an old wooden door secured by a large padlock. Lau produced the key and we entered. There was a small table in the centre of the room, the walls of which were lined by benches similar to those used for gym lessons in the KJC school hall. Upon the walls hung various pennants and banners in red with serrated black borders and black writing upon them. Opposite the door was an altar bearing a small idol of a male god with a fierce-looking face, one candle alight before it.

“God Kwan Ti,” Lau explained. “This is my god.”

Yet it was something other than the banners and Kwan Ti that caught my eye. Hung between the banners were macabre, sadistically ferocious-looking weapons. One was a chain with a ball set with spikes at one end; another chain culminated in a spear-point blade. Balancing in a wooden rack were a number of metal six-pointed stars of varying diameters. From their shine, the points were clearly well sharpened.

“What is this place?” I enquired. Lau made no attempt to explain but said, “Gweilo no come here. You vew’y lucky boy I show you.”

As we moved through the big room in the building, a boy of about my age descended the stairs carrying a tray upon which there was a small lamp, several minute bowls, a number of metal needles and the most bizarre pipe. My grandfather always smoked a simple-looking Dunhill with a wooden bowl; my father, on occasion, smoked a swan-necked Meerschaum. This was very different. A good fifteen inches long, the stem was made of bamboo, the mouthpiece on milky-coloured jade or soapstone. The bowl was a curious device for it had nowhere that I could see in which to put the tobacco; indeed, it appeared to be a virtually sealed container. All there was in it was a tiny hole in the top.

“Nga pin [opium]?” I asked tentatively.

Lau stared at me. “How you know nga pin?”

“I know,” I shrugged, still not knowing exactly what it was.

He took me by the hand and led me up the stairs. “No talk,” he whispered. As my head rose above the first-floor level, I saw half a dozen men lying on the kangs [beds]. All but one were asleep on their sides, their hands tucked between their drawn-up legs or under their necks. One snored, another intermittently moaned softly, the only other sound was their breathing. The air had a strange and familiar perfume and it was at least a minute before I recognised it as the scent of the rickshaw coolies’ pipes on my first night in Hong Kong.

The man who was awake had by his head one of the little lamps, the flame contained within a thick glass funnel. The boy moved past us, giving me a quick and puzzled look. He went to the man and impaled a small bead of something on one of the needles, starting to revolve it in the lamp flame: then, very adroitly, he placed it over the tiny hole in the pipe bowl, passing it to the man who lay on his side and sucked evenly on the pipe. After doing this three times, the man lay down and closed his eyes. The boy removed the pipe and blew out the lamp.

“We go,” Lau murmured. Once we were outside, I asked, “what was that man doing?” “He smoke opium,” Lau answered. “Get dream, go good time-side.”

I stepped over the characteristic high lintel to find myself in a small entrance hall. To one side, seated at a tiny desk, was an old woman. Lau greeted her and they spoke in quiet voices until Lau stepped aside to reveal my presence. The moment she saw me, the woman cackled asthmatically and entered into a conversation with Lau that was filled with much suppressed hilarity and sidelong glances at me.

Feeling I was being made the butt of their humour, and not quite knowing how to react, I looked down. It was then I saw the old woman’s feet projecting out from under the desk. They were minute, encased in scuffed brocade slippers no bigger than a baby’s knitted bootees. The toe end was squared off like the ballet dancing pumps girls wore at school.

“Lotus foot,” Lau said, following my line of sight. “Long time before, China-side, men say tiny foot on lady ve’y . . .” he paused, searching for a word “. . . booty full. Like lotus flower.” I nodded sagely but could not see how, with the wildest imagination, a foot could resemble a flower.

After the obligatory caress of my golden hair by the old woman Lau led me down a corridor of dark wooden panelling, passing a number of narrow doors split like those of a stable. At intervals, dim bulbs provided the minimum of light. Towards the end of the passage-way, Lau stopped at a door and knocked. The top half opened and a pretty Chinese woman looked out. She wore an imperial yellow silk cheongsam, her hair piled up and held in place by a soapstone pin. As they spoke in subdued voices, she did not take her eyes off me for an instant. Needless to say, she reached out to touch my head.

There was the sound of a pulling bolt and the bottom half of the door opened to reveal a panelled cubicle lit by a red lamp in front of a tiny shrine. The only furniture was a wide kang raised higher than normal from the floor and a Chinese-style chair. Upon the kang were a tangle of quilts and a Chinese paperback book on the cover of which were portrayed a man and a woman kissing. On a shelf below the shrine was a row of Chinese scent bottles. “You go in,” Lau instructed. “Sit down.”

I perched on the rim of the kang. The young woman sat next to me, talking to Lau through the door but all the while watching me. The air – and the young woman – smelt of orange blossom slightly tainted with sweat.

“You know this place?” Lau enquired at length. “No know,” I admitted. “This old place,” Lau continued. “Maybe more one hundred year. Long time before place for rich man come jig-a-jig. Fam’us place. Man come long way from Canton jig-a-jig here. Fam’us girl stayed here long time before.” To lend meaning to his words, he put his thumb between his index and middle finger and wiggled it. The young woman giggled. I was lost as to its meaning. “You lo know jig-a-jig?” Lau asked. I shook my head. “Lo ploblum,” he replied dismissively. “Come! We go now.” He said goodbye to the young woman. I added my own choi kin. She burst into a peal of giggles, put her hand demurely to her mouth to stifle them and closed the doors on us.

Whenever I visited Kowloon Walled City, Lau was always there, ready to guide me around, drink tea with me and talk. When, after a few months, the place started to lose its appeal and I stopped visiting. I never saw him again. It was some years before I realised that he and Ho had been Triad members – Chinese Mafiosi – infamous for their utter ruthlessness, whose secret fraternity ran the opium dens and brothels, and held Kowloon Walled City in its thrall. The semi-subterranean room had been their meeting place.